The Southwest Ohio Regional Transit Authority (SORTA) announced their selection for a new Chief Executive Officer and General Manager, to fill Terry Garcia Crews’ vacated position, earlier this month. Dwight Ferrell was the person tapped for the position, and will take over effective January 5, 2015.

The Southwest Ohio Regional Transit Authority (SORTA) announced their selection for a new Chief Executive Officer and General Manager, to fill Terry Garcia Crews’ vacated position, earlier this month. Dwight Ferrell was the person tapped for the position, and will take over effective January 5, 2015.

Ferrell boasts a long a diverse career in the transit industry. He will join Metro following his service as the County Manager for Fulton County, Georgia, where he oversaw more than 5,000 employees along with the county’s state and federal legislative agenda. In addition to that, Ferrell also previously worked with Atlanta’s largest transit agency as the Deputy General Manager and Chief Operating Officer at MARTA – America’s ninth largest transit system.

Ferrell’s background extends beyond the Atlanta region and includes transportation experience in Austin, Dallas, New Orleans and Philadelphia. According to Metro officials, he is also an active member of the American Public Transportation Association, Conference of Minority Transportation Officials, and Transportation Research Board.

Prior to taking over as Metro’s new CEO, Ferrell kindly agreed to an interview with UrbanCincy. The following interview was conducted on December 22, and is included below in its entirety.

Randy Simes: Coming from Atlanta, and having worked on their streetcar project, did you and Paul Grether, Metro’s current Rail Services Manager who previously worked as MARTA’s Streetcar Development Manager, ever work together? If so, how was your experience working with him, and how might that experience be beneficial moving forward with the operations of the Cincinnati Streetcar?

Dwight Ferrell: I did work with Paul and have the highest regard for his knowledge about rail transit. Paul serves as the chair of the American Public Transportation Association’s streetcar committee, which is in Cincinnati this week to see the Cincinnati Streetcar construction.

Cincinnati is fortunate to have Paul working on this project. I am confident that under his leadership all Federal requirements will be followed and we’ll be ready to operate the streetcar in 2016.

RS: If there is one thing from your experience with MARTA that you could copy and duplicate at Metro, what would it be and why?

DF: I really believe in performance management. It’s important for the community to know how we’re doing and for us to be transparent.

RS: When Atlanta pursued federal funding for its streetcar, there was the idea that the city needed to choose between seeking funding for rail transit for the BeltLine or the streetcar. Ultimately Atlanta went with the streetcar. If presented with a similar dilemma in Cincinnati, about a second phase of the streetcar or the Wasson Line, which do you think you would be more inclined to support and why?

DF: These are local decisions based on many factors, and it’s too early for me to evaluate the merits of projects in Cincinnati. The process of securing Federal funding for rail projects requires intensive analysis and review to determine if a project would be eligible for funding to move forward. It’s a highly competitive funding arena.

RS: MARTA was dealt a blow with the defeat of TSPLOST, but gained a big victory recently when Clayton County voters approved an expansion of MARTA to their county. With SORTA exploring potential transit tax increases and service expansions of its own, what do you think should be learned from those two very different experiences in Atlanta?

DF: Each region is unique. I need to get to know what the community wants in terms of expanded transit, so any talk of funding increases is premature at this time. That said, Metro is a status quo system; if we add service somewhere, it has to be decreased somewhere else. We can’t add service to meet the community’s need for access to jobs without more funding.

RS: Metro*Plus service has seemed to be a hit since its initial launch. Metro has publicly stated its interest in establishing several more Metro*Plus corridors, but what is your take on reducing stop frequency along all routes in order to improve travel time?

DF: Limited stop services like Metro*Plus are just one tool in the toolbox, and they work great in some applications. They offer a faster ride, but speed is not always the only consideration. For some neighborhoods, convenient access to a bus stop is critical, especially for older riders and riders with disabilities.

RS: How do you envision Metro’s existing and future bus service working together with not only the first phase of the Cincinnati Streetcar, but other potential rail transit in the region?

DF: It is imperative that Metro bus service and other modes function as an integrated transit system without redundancy. The goal should be a seamless transit experience. This means easy transfers between modes, a coordinated fare structure, shared infrastructure like ticket vending machines and back-office technology related for emergency response and vehicle movement.

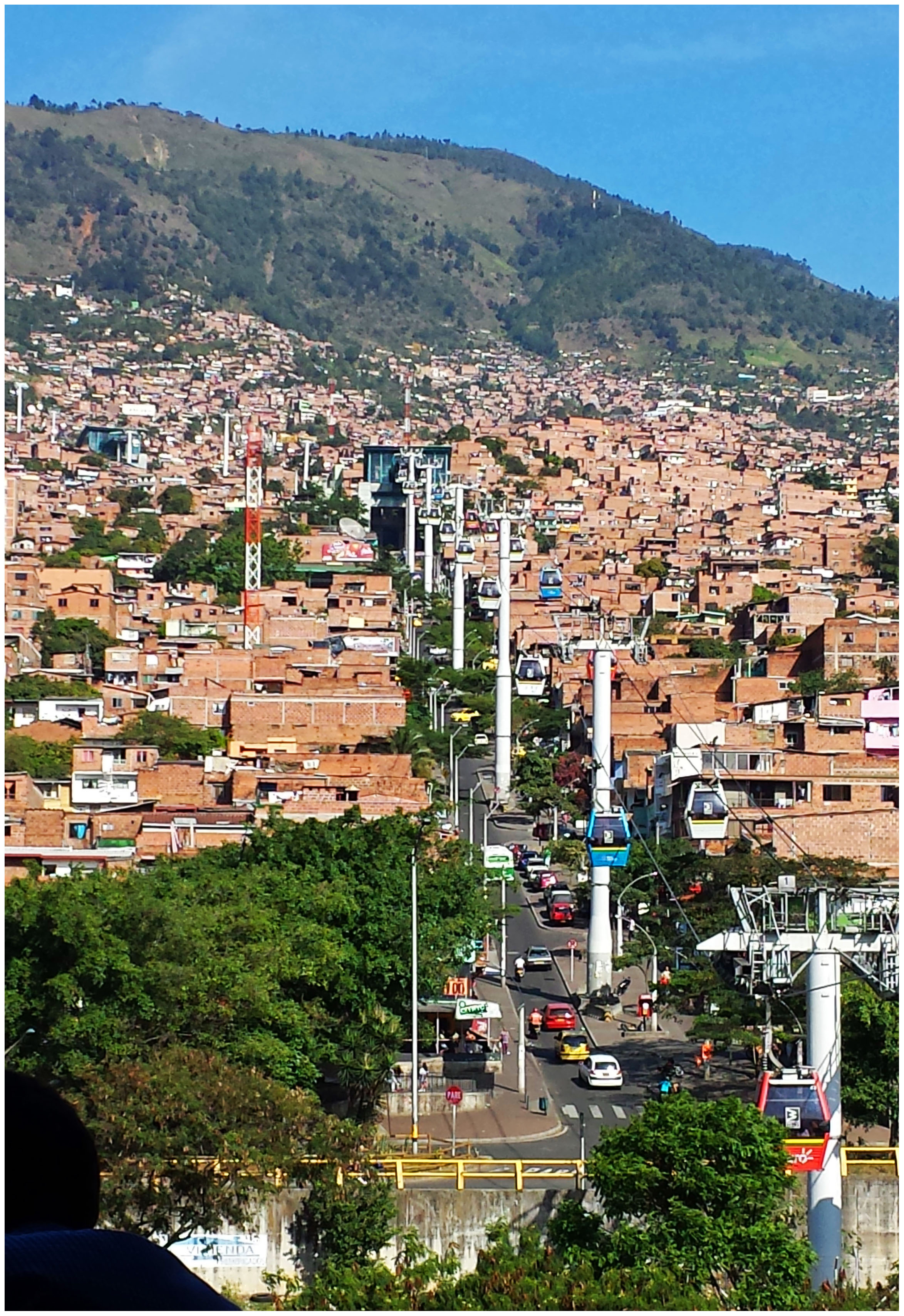

RS: The best-scoring bus rapid transit line in North America is Cleveland’s HealthLine, but it scores a mere 63/100 points. Do you think true BRT, as defined by what has been built in Bogotá and Curitiba, is appropriate for North American cities? Furthermore, would you support the development of such a corridor in Cincinnati?

DF: BRT is appropriate in some cities and some applications depending on the objective. I need to get to know Cincinnati before judging whether BRT is right for this community. Federal funding for BRT has become more restrictive in recent years and finding exclusive right of way is sometimes difficult in older cities with high density. The decision whether or not to build BRT is really about what works for Cincinnati.

RS: How does Cincinnati’s cold weather and its hills differentiate it from your past experience? How do these conditions impact how you run a transit system?

DF: I worked at SEPTA in Philadelphia, so I do have some familiarity with what winter can mean to transit in northern cities. Transit is adaptive — if a hill is impassable, we find a way around. We’re all dependent on the road conditions and we stress safety. Today we have the ability to use social media to keep customers updated on what’s happening with their service, which is a benefit.

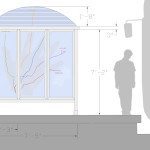

RS: A topic UrbanCincy has continually raised up for discussion is what could/should be done with the Riverfront Transit Center. A variety of ideas have been suggested, but in your opinion what do you think is the future of that facility?

DF: I visited the Riverfront Transit Center when I was in town last week, and it is an impressive facility. It’s used every weekday, about every 15 to 30 minutes, for Metro*Plus service and it’s used for Bengals and Reds games and special events. It’s my understanding that the All-Star Game coming to Cincinnati next summer will depend heavily on this facility for staging of buses and other vehicles. That’s what the Riverfront Transit Center was built to do: serve Cincinnati’s redeveloped riverfront venues and events. Long term, our goal is to maximize its use.

RS: What transit system in the world impresses you the most and why?

DF: Each system has its own appeal. Of course, mega-systems like New York City and Washington D.C. are impressive because of their sheer size and the incredible number of people they move every day. I think the most impressive systems are the ones that allow people to move around without the need for a car.

RS: Finally, what first made you interested in transit and want to pursue a career in the industry?

DF: I was 23 when I started as a bus driver in Dallas, and I was a bus driver for 10 years. When the merger occurred with DART, new opportunities opened up for me in management. My career progressed to the C-suite and those positions allowed me to work at the most senior levels of transit management across the country. I feel blessed to have found a career and an industry that I am passionate about. Metro recently started the John W. Blanton internship to provide an opportunity for college students to experience the transit industry as a career path, and I support that effort.

Dwight Ferrell holds a BA in Business Administration from Huston-Tillotson University. He can be reached at dferrell@go-metro.com.