Since 2013, the number of pedestrians killed or injured in car crashes in Cincinnati has been on the rise. In 2018 alone, 428 pedestrians were struck by vehicles in the city, including 13 Cincinnati Public Schools students. One of those students, 15-year-old Gabriella Christine Rodriguez, was tragically killed while crossing Harrison Avenue on her way to school.

On January 18, Mayor John Cranley proposed $900,000 worth of pedestrian safety improvements across the city, including the addition of new crosswalks, improved signage, sidewalk bump-outs, and the conversion of some off-peak parking lanes into full-time parking lanes. Some of these improvements are located near schools where students are likely to be crossing the street. Others are located in neighborhoods like Pleasant Ridge where residents have been asking the city for traffic calming initiatives for years.

Notably absent from Mayor Cranley’s pedestrian safety announcement, however, was any mention of the Liberty Street Safety Improvement Project.

A brief history of the Liberty Street road diet

In the 1950s, Liberty Street was widened from two lanes to its current seven-lane configuration in order to funnel automobile traffic to the newly built Millcreek Expressway and Northeast Expressway, which are now known as I-75 and I-71. Hundreds of properties in Over-the-Rhine and Pendleton were purchased and demolished to accommodate the widening project, which cost $1.3 million at the time, the equivalent of $12.3 million in today’s dollars. Within years of the project’s completion, residents were complaining that the widened street was unsafe for school children to cross.

A “road diet” was proposed in the 2011 Brewery District Master Plan as a way to reconnect the Brewery District in northern Over-the-Rhine with the rest of the neighborhood. In April 2013, City Council directed the Department of Transportation and Engineering (DOTE) to begin studying the idea. DOTE hosted several community input sessions in 2015 and 2016, studied several options for improving the street, and settled on a plan to narrow the seven-lane street down to five lanes. The city presented a “final schematic design” for what became known as the Liberty Street Safety Improvement Project in October 2017.

However, in August 2018, it was revealed that city administration had “paused” the project. An August 7 memo released by then-Acting City Manager Patrick Duhaney explained that the project was paused due to concerns that a slimmed-down Liberty Street couldn’t handle the traffic headed to and from FC Cincinnati’s new West End stadium, and a funding gap due to the need to relocate a water main for the project. In a subsequent memo released on August 31, Duhaney recommended an “Administration Preferred Option” that would “scale back the project to install bump-outs at each intersection” without any reduction in the street’s width.

The “Administration Preferred Option” for Liberty Street

In October, City Council allocated more funding to the project to cover the cost of moving the water main and directed the administration to proceed with the road diet. However, it seems that city administration has began considering several new options that would keep Liberty Street at its current width. According to city documents and emails obtained by UrbanCincy, the following options now appear to now be under consideration:

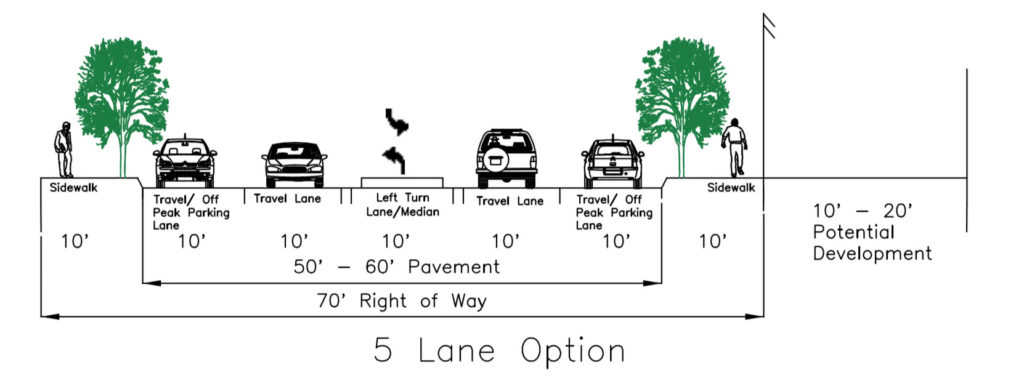

- The 5 Lane Option was the “final” plan presented to the Over-the-Rhine Community Council in October 2017.

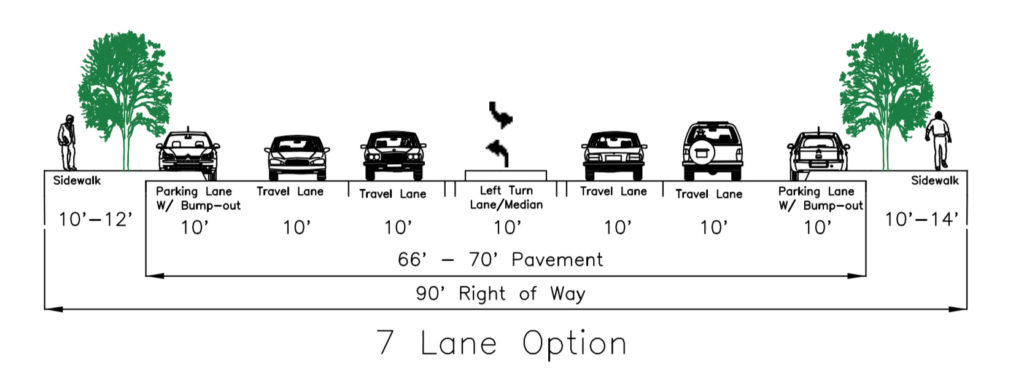

- The 7 Lane Option would keep Liberty Street’s current width and configuration, but add bump-outs at each major intersection, slightly reducing the crossing distance for pedestrians.

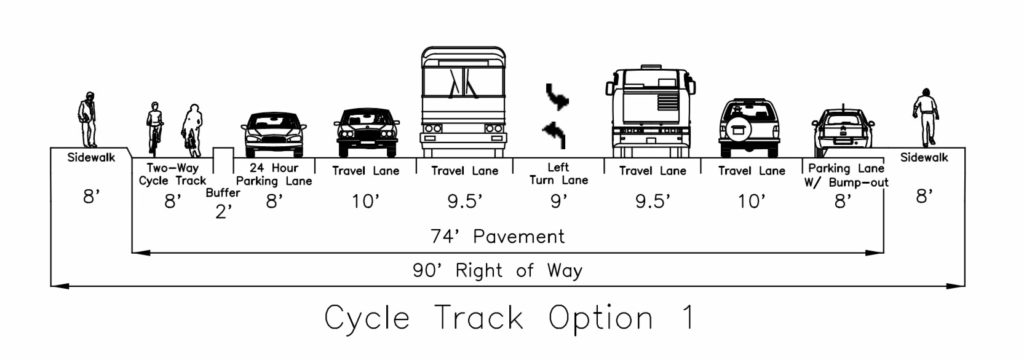

- Cycle Track Option 1 would add an 8 foot wide bidirectional cycle track on one side of the street and maintain 7 lanes of automobile traffic in the configuration that exists today but with narrower lanes. Sidewalks would be narrowed to 8 feet.

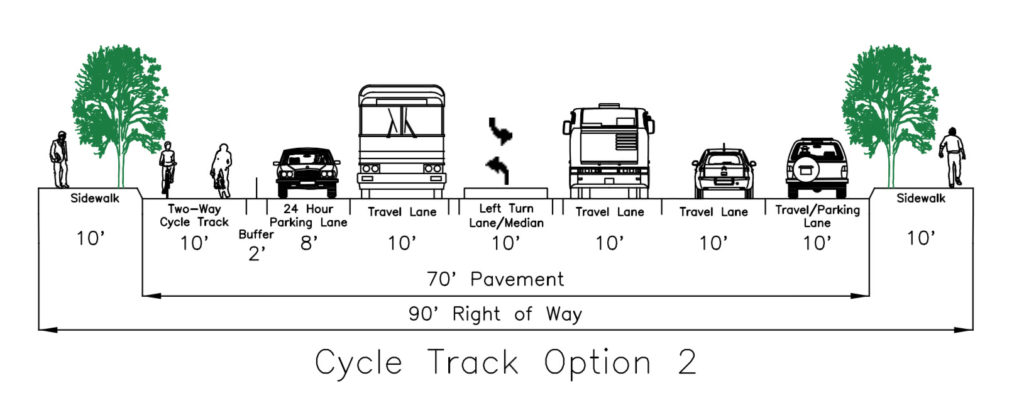

- Cycle Track Option 2 would add a 10 foot wide bidirectional cycle track on one side of the street and maintain 6 lanes of automobile traffic. In one direction, the street would have two vehicle travel lanes and a full-time parking lane. In the other direction, it would have one vehicle travel lane and an “off-peak” parking lane that would convert to a travel lane during rush hour(s). (Note: In this draft document, the parking lanes appear to be mislabeled. The parking lane on the left should be labeled “Travel/Parking Lane” and the parking lane on the right should be labeled “24 Hour Parking Lane”.)

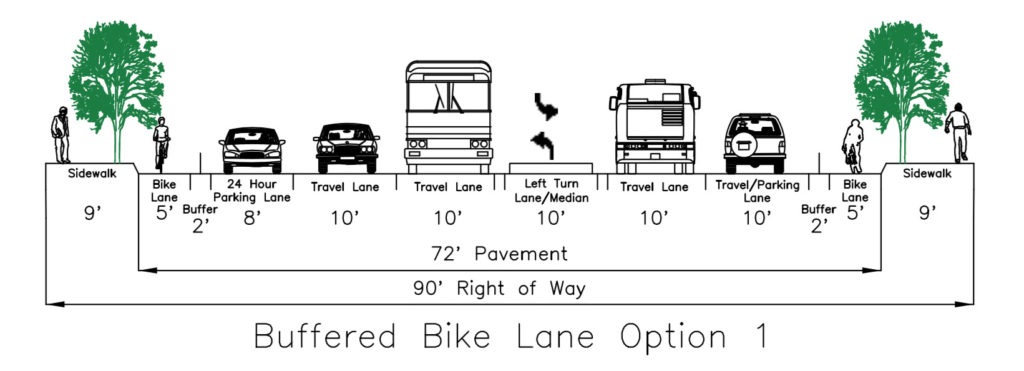

- Buffered Bike Lane Option 1 would add a 5 foot wide bike lane on each side of the street, located between the sidewalk and parked cars, and maintain 6 lanes of automobile traffic. In one direction, the street would have two vehicle travel lanes and a full-time parking lane. In the other direction, it would have one vehicle travel lane and an “off-peak” parking lane that would convert to a travel lane during rush hour(s). Sidewalks would be narrowed to 9 feet.

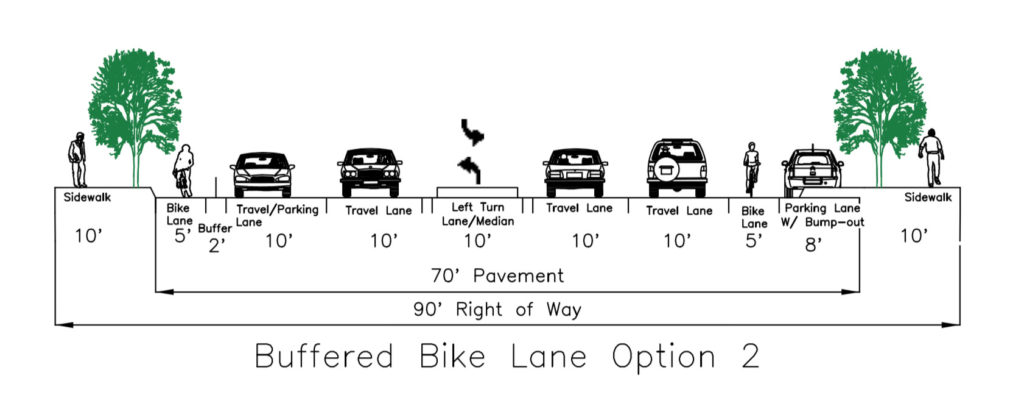

- Buffered Bike Lane Option 2 is similar to the previous option, except that in one direction of travel, the bike lane and full-time parking lane have swapped positions. While this allows sidewalk bump-outs to be added on one side of the street, reducing the crossing distance for pedestrians, it is also more dangerous for cyclists, who will be riding next to fast-moving cars rather than in a protected zone between parked cars and the sidewalk.

While the 2011 Brewery District Master Plan proposed adding bike lanes to Liberty Street, DOTE didn’t spend much time studying them due to lukewarm response at the public input sessions. According to a city document, “Bikes, pedestrian, and vehicular needs, among others, were all prioritized based on data and community feedback. Bike lanes were determined to not be a high priority and were eliminated from the options very early in the process. The top priority was pedestrian safety with a focus on the long street crossings that exist today.”

The idea of adding bike lanes returned in early October 2018, when city staff began to “brainstorm different scenarios for Liberty Street that do not involve moving the water main,” according to an email sent by a city staff member. The bike lane options would allow for some safety improvements to be implemented without narrowing the total width of the street, so they wouldn’t require the water main to be moved. However, these options would not achieve the “top priority” of the original project: significantly reducing the pedestrian crossing distance and reconnecting the northern and southern halves of the neighborhood.

Now that City Council has now provided the necessary funding to move the water main and narrow the street, it would seem that the primary reason for the ongoing “pause” and re-evaluation of the project is the city administration’s desire to maintain maximum vehicular access to the new FC Cincinnati stadium in the West End. In October 2018, Mayor John Cranley dismissed what he called “conspiracy theories” that FC Cincinnati had anything to do with the decision. And while we uncovered no evidence that FC Cincinnati’s ownership asked the city to kill the road diet, it does seem that DOTE is prioritizing traffic headed to and from the stadium above other users of the street.

In an email from May 2018, one DOTE staff member explained, “We anticipate having a Event Timing Plan for the signals that will favor funneling vehicles towards the stadium prior to the game and away from after the game.” So while a larger traffic study of the downtown street grid, which primarily focuses on improvements for transit riders and pedestrians, is stuck in political gridlock, traffic signal timing changes to speed cars down Liberty Street have been fast-tracked.

Additionally, the DOTE staff member explained that “Central Parkway is not a good conductor of large event traffic” and that the city wants to “try to minimize the vehicular traffic on the N/S portion of Central Parkway as this will have a very large number of pedestrians.” This explains the city administration’s desire to close a portion of Central Parkway on game days, which would have the effect of funneling even more highway-bound traffic down Liberty Street.

What does the Liberty Street “pause” tell us about the city’s commitment to Vision Zero?

During Mayor John Cranley’s pedestrian safety announcement in January, he mentioned that Cincinnati would move forward with implementing a Vision Zero program. While few specifics were given, Vision Zero programs typically have the goal of reducing the number of traffic-related deaths and serious injuries by rethinking how streets are designed in order to prioritize all users—including pedestrians, cyclists, and transit riders—instead of designing them to move as many cars as possible, as fast as possible. Vision Zero programs often include reducing speed limits, reconfiguring overly-wide streets and intersections, and adding new crosswalks, sidewalk bump-outs, and bike lanes.

Vision Zero policies have been implemented by dozens of cities across the country and around the world, and have resulted in measurable safety improvements. New York City adopted Vision Zero in 2014 and has experienced a decrease in pedestrian fatalities for five consecutive years. The benefits aren’t limited to big cities like New York, though. Smaller Ohio cities like Canton and Lima have also incorporated Vision Zero-style traffic calming techniques into recent street redesigns.

Road diet in Canton, Ohio

Road diet in Lima, Ohio

In order for a Vision Zero policy to be effective, it can’t just be a slogan. It can’t just be a one-time expenditure of $900,000 for a handful of pedestrian safety improvements that are easy political wins. It has to be a comprehensive set of policies that require DOTE to take pedestrians, cyclists, and transit riders into consideration every time a street is designed. It requires that the city seek input from residents about changes they want to see on their streets and turn those ideas into reality. Sometimes, it will require that the city makes decisions that inconvenience drivers in minor ways—reducing speed limits in neighborhood business districts and on residential streets, increasing enforcement of traffic laws, and perhaps losing a few on-street parking spaces to add new crosswalks—in order to make streets dramatically safer for everyone.

The Liberty Street Safety Improvement Project is a slam dunk Vision Zero project. It is widely supported by neighborhood residents and has been fully funded by City Council. And yet, the city administration seems to have decided at the eleventh hour that the need to move cars to and from the new FC Cincinnati stadium as fast as possible is a higher priority than desires of residents who want a safer street and a reconnected neighborhood.

If the city implements a Vision Zero program, it will be faced with this same conflict over and over again. Neighborhood residents want a safer street with calmer traffic, but drivers want to get from Point A to Point B as quickly as possible without slowing down. With Liberty Street, the city administration has chosen to side with drivers. If this is representative of future decisions that the city administration and DOTE will make, Cincinnati’s Vision Zero program will not be successful.