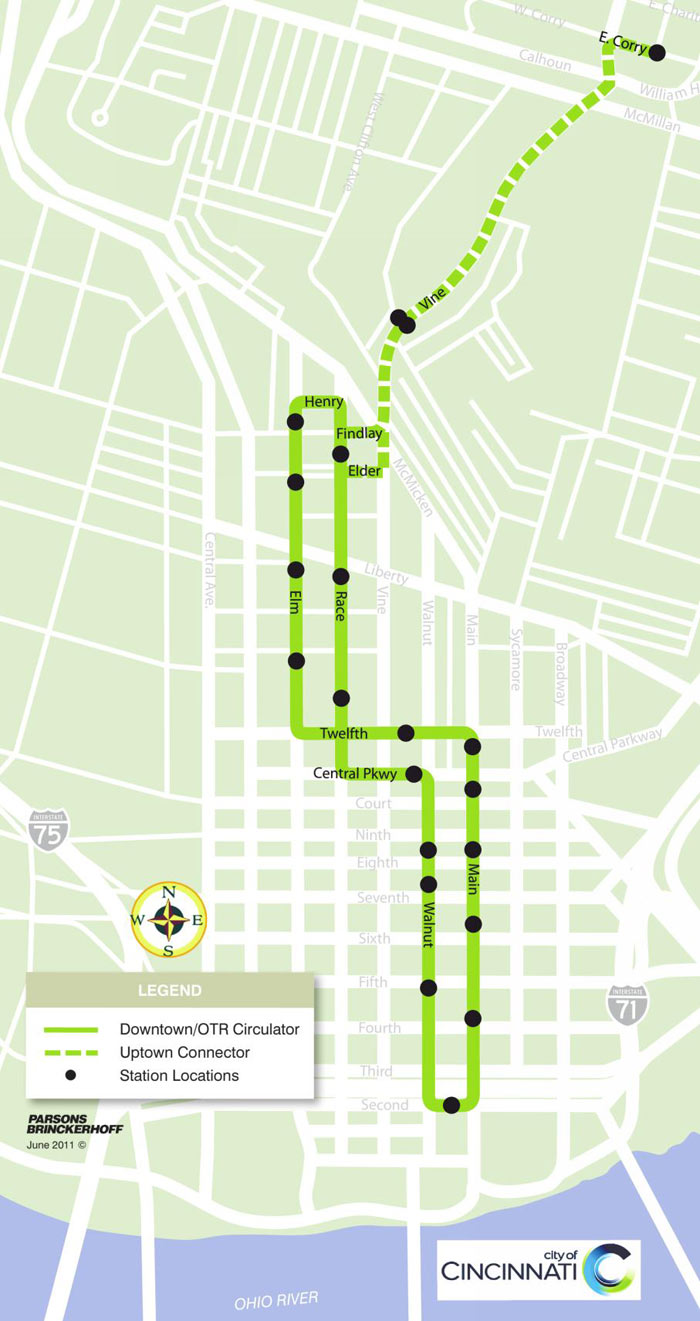

There is perhaps no more controversial word to utter in Cincinnati than streetcar. The roughly three-mile rail project connects the riverfront to Over-the-Rhine’s Findlay Market, passing several points of interest and centers of employment along the way. The total cost for the streetcar is roughly $100 million, and it is fully funded without taxpayer assistance.

To anyone familiar with transportation projects, this price tag is on the low end of the spectrum, and actually appears to be quite affordable when compared to highway construction and more comprehensive light and heavy rail systems, which both often have project costs well exceeding a billion dollars.

In spite of this, the Cincinnati Streetcar project has been met with a very vocal public opposition from day one. The project has faced and defeated two ballot initiatives aimed at stopping the project completely, has adapted to a smaller route after having more than $50 million in state funding revoked, and has generally persevered through every challenge the opposition has created.

The question I want to answer is not whether the streetcar is a good idea; nor do I want to speculate on the future success or failure of the project. What is far more compelling of an idea to explore is the root causes of the unrelenting opposition to what is actually a modest and simple transportation and economic development project.

Perhaps no better city serves as a juxtaposition to the Cincinnati experience than Los Angeles. Having lived, worked, and studied urban planning in LA for the past 4.5 years; I was able to witness firsthand the differences from Cincinnati in the attitudes towards transit, and more generally, the city itself.

Passengers board the Blue Line LRT in Los Angeles. Photo provided by John Yung for UrbanCincy.

Passengers board the Blue Line LRT in Los Angeles. Photo provided by John Yung for UrbanCincy.

In 2008, over 67% of Los Angeles County residents approved Measure R, a 30-year half-cent sales tax increase to support transportation projects. As a result of the passage of Measure R, LA is now in the process of building:

- The so called “subway to the sea” connecting Downtown LA to Santa Monica;

- An extension of the Green Line light rail line to connect to Los Angeles International Airport;

- An extension of the Gold Line light rail line to serve the far eastern suburbs; and

- Phase two of the Expo light rail line connecting Culver City with Santa Monica (phase one connected Downtown LA with Culver City, and opened in 2012).

Additionally, a downtown streetcar project (sound familiar?) was proposed a few years ago, and in late 2012, nearly 73% of downtown residents voted to create a special, localized tax district to partially fund the project.

In 2013, Los Angeles has transformed from a city known for its sprawl and obsession with freeways and cars, to a city with multiple rail lines under construction simultaneously and a regional population that has twice voted in a super-majority to increase their tax burden to fund transit. Instead of simply chalking up the different experiences in Cincinnati and LA as being the result of differing demographics, I think that there are two main underlying differences between the cities that help explain the reactions to transit.

High Growth vs. Low Growth

While the City of Cincinnati has been hemorrhaging population since the 1970s, the metropolitan area has seen slow and steady population growth. Although slow growth is better than regional decline, a la Cleveland and Pittsburgh, the growth rate of the Cincinnati region pales in comparison to growth experienced in the Southern and Western parts of the country that constitute the Sunbelt.

Conversely, the Los Angeles story has been one of explosive growth at both the city and regional level since the 1940s. The slow growth of Cincinnati creates a situation where municipalities in the region compete with each other not just for jobs, but also residents, potential customers for businesses, and resources. The insecurities of slow growth repeatedly surface in the opposition to the streetcar. “Why not spend $100 million in my neighborhood?”

The streetcar represents an investment in part of the city that will almost assuredly give it an advantage over other parts of the metro area. As such, it is seen as a threat to the population and employment bases to many communities in the region. In Los Angeles, however, while there is still competition among municipalities, the situation is not a zero sum game, and therefore does not elicit the same threatened response that we see in Cincinnati.

Regionalism

The second of the two underlying factors that help explain the difference in attitudes toward transit in Cincinnati and Los Angeles is regionalism. Los Angeles is often described as the prototypical polycentric city. Rather than one core, Southern California is dotted with hubs of commerce, retail, and population. The city of Los Angeles itself has multiple clusters, and there are several other cities in the region such as Pasadena, Glendale, Santa Monica, Long Beach, and Anaheim that serve as nodes on the regional map.

A result of this polycentricity is interdependence among different parts of the region. Someone who lives in Burbank might work in Downtown Los Angeles, shop in Pasadena, go to the beach in Santa Monica, and take their kids to Disneyland in Anaheim. When you think regionally, it is easier to view the improvements of one community as indirectly benefitting yourself.

As most regions in 2013, Cincinnati is also increasingly polycentric. However, there is a strong monocentric legacy in Cincinnati; where downtown was the undeniable heart and hub of the region. Neighborhoods take pride in their unique identities, and often times regionalism is viewed skeptically, as embracing it necessitates a departure away from the hyper-localism that Cincinnati prides itself on. With this type of perspective, it is harder for individuals to see how a transit improvement elsewhere in the region would benefit them.

The monocentric legacy of Cincinnati also has led many people to feel attached to downtown in a way that does not exist in Los Angeles. Much of the streetcar opposition is from people who live outside of the City of Cincinnati, from people who feel that, despite living far away from the project, they still have a right to comment on it because downtown is perceived as being almost a public good for the region to consume.

In Los Angeles, opposition to transit projects seems to come from groups that have a specific issue that they object to. For example, the Expo Line came under attack by environmental groups when Metro announced that a sizeable number of trees had to be removed for construction of the line. An environmental group having a problem with trees being cut down is a logical complaint that is able to be placated relatively easily. In Cincinnati, stopping the city from progressing seems to be an interest group in itself, with broad support from a variety of different populations. This type of opposition is what stymies Cincinnati, and keeps the region in relative stagnation.

There are deep, underlying issues that contribute to these attitudes- far more than I could cover in this post, but I believe that low growth and lack of regional thinking are the two underlying issues at the root of much of the opposition to the Cincinnati Streetcar. Los Angeles, for much of its existence, was the poster child for sprawl, automobile dependence, air pollution, and many other associations that are incongruent with a pro-transit city. Somewhere in the past 20 or so years, LA made a switch.

Perhaps it was a re-exposure to rail transit following the construction of the Red Line subway in 1993, LA’s first rail line since the removal of the extensive streetcar network that covered the city. Or maybe Angelenos finally got fed up with the infamous traffic that has snarled Southern California for decades. Whatever the tipping point was, Los Angeles has positioned itself as a leader of transit in the 21st century. The high growth Los Angeles region is transforming before our eyes. It’s time for Cincinnati to take a look.

This guest editorial was authored by Patrick Whalen – a Cincinnati native who currently lives in the city’s Mt. Adams neighborhood. Patrick is a member of the Urban Land Institute’s Mission Advancement Committee, and graduated from the University of Southern California’s Price School of Public Policy. He now works for Urban Fast Forward – an urban real estate and planning firm based in Cincinnati. If you would like to have your thoughts published on UrbanCincy you can do so by submitting your guest editorial to urbancincy@gmail.com.