The beautiful Greek islands throughout the Aegean Sea are often known for their stunning landscapes, crystal clear blue water and their ancient development patterns often dating back to the Bronze Age between 3000-2000 BC. These ancient development patterns, while picturesque, also offer contemporary lessons on how to approach development in space-constrained locations.

The beautiful Greek islands throughout the Aegean Sea are often known for their stunning landscapes, crystal clear blue water and their ancient development patterns often dating back to the Bronze Age between 3000-2000 BC. These ancient development patterns, while picturesque, also offer contemporary lessons on how to approach development in space-constrained locations.

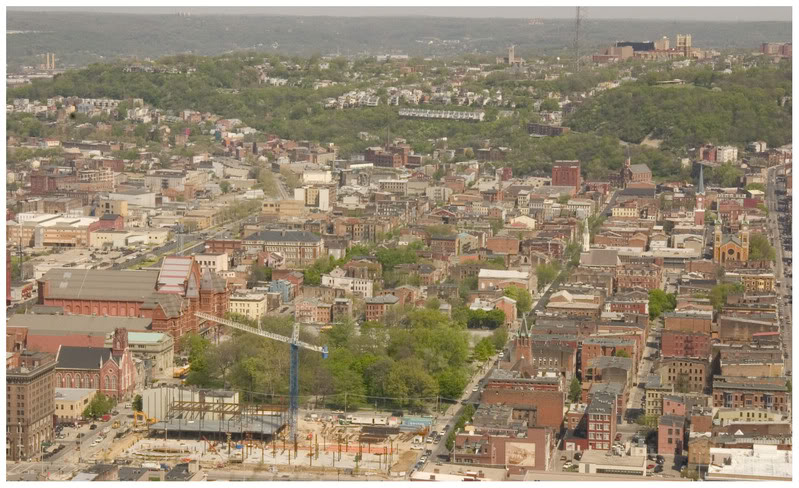

In America, the problem is not limited land as experienced on the Greek islands, but rather, it is limited urban real estate. This dilemma often sends buildings and prices higher, with the most easily developed land to go first. Consequently, development often sprawls outward before communities fully maximize development possibilities within their urban centers.

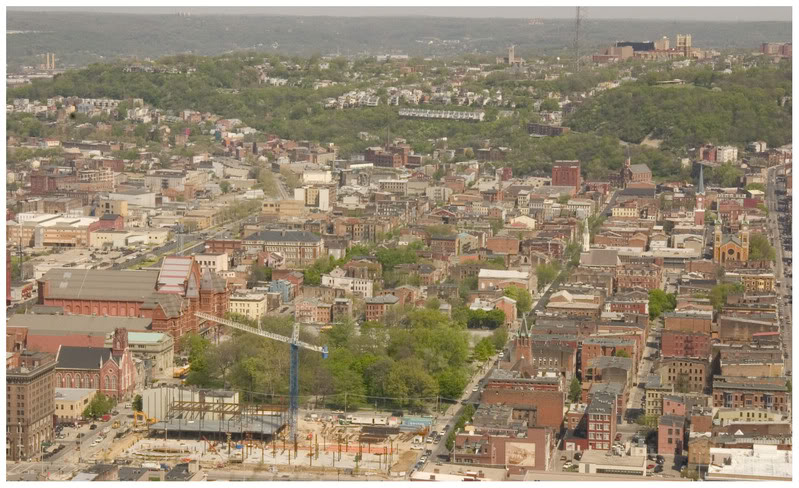

In Cincinnati this scenario is most profound with the city’s hillsides. Early settlers built their homes, businesses and industry along the Ohio River for transportation reasons, and throughout “the basin” in order to take advantage of relatively flat and developable land. Over time Cincinnatians became more mobile and moved up on top of the hills developing areas like Price Hill, the Uptown neighborhoods, Mt. Lookout, Hyde Park and even Mt. Adams. Since then development has shifted even further out to more contemporary suburbs and exurban communities now gobbling up precious farm land in all directions. In the mean time, Cincinnati’s many hillsides have been largely ignored and allowed to either be over- or under-developed.

According to The Hillside Trust, 15 square miles, or 18%, of Cincinnati’s total land area is hillsides. Of the nearly 265,000 acres of land in Hamilton County approximately 60,043 acres, or 23%, consist of hillsides with similar percentages found in Northern Kentucky’s three primary counties – Campbell, Kenton and Boone.

On the Greek islands the exact opposite approach was taken after early Bronze Age settlers developed their communities. Those inhabitants quickly realized that they had to preserve their limited amount of tillable land, and as a result shifted their settlement patterns to the hillsides so that the other, more productive, land could be used for agricultural purposes. While less relevant to non-Medieval cultures like America, those living on the Greek islands also developed their communities in steep valleys where water would run-off from the higher lands towards to sea as a means of safety since these areas could often not be seen by passing ships.

On Santorini, the flat lands are largely preserved for agricultural purposes [LEFT] while the the densely built Thira is located directly on the caldera [RIGHT].

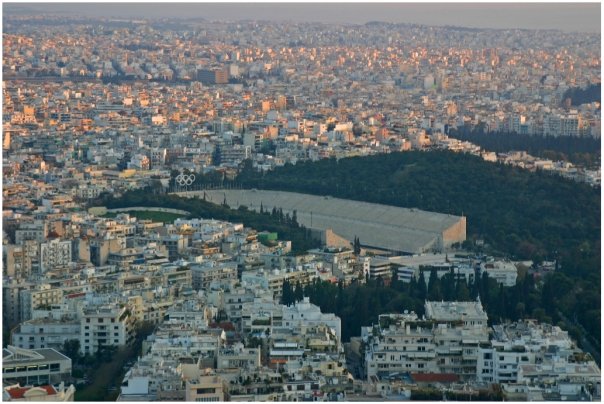

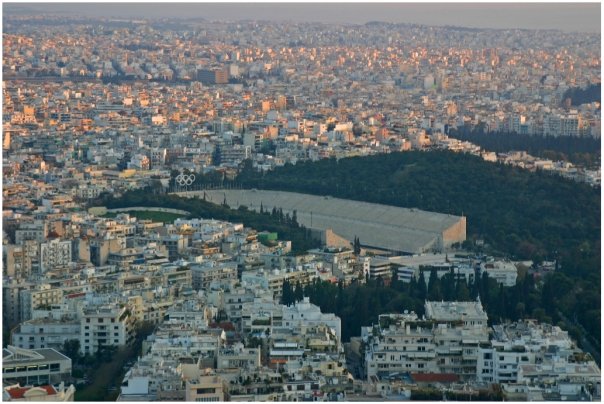

The development strategies found in Greece’s large urban center, Athens, are probably the most relevant as the city has developed in a way to maximize their urban center in a way to preserve surrounding natural resources.

Athens is the capital of Greece and the hub of its economic activities. The city accounts for roughly one-third of the country’s total population while dating back to 3,000 BC. Similar to Cincinnati, Athens is located within the Attica Basic that is surrounded by mountains to the north, northeast, east and west with the Saronic Gulf situated like the Ohio River to the southwest. The natural boundaries helped to influence dense development patterns in the Greek capital much like early Cincinnati. Unlike Cincinnati though, Athens has largely maintained these natural barriers over time as a means for continuing dense, urban development that concentrates the region’s growth into a relatively small area.

The balance struck in Athens is one of sustainability impacts. The conquering development patterns on natural hillside landscapes are as non-sustainable environmentally as they are sustainable economically in their immediate setting. The environmental gains are seen through the preservation of natural resources outside of the urban center. Similar sustainability processes can be seen in other major cities around the world including New York City which boasts one of the lowest carbon footprints per capita even though the city made a previously natural habitat virtually unrecognizable.

Athens’ dominating urban landscape does not yield to the natural landscape in its urban core [LEFT] while Cincinnati’s urban landscape weakens immediately at its hillsides [RIGHT].

A more densely built urban environment in Cincinnati needs to occur for it to experience similar economic and environmental sustainability benefits. The region’s resources are spread too thin to provide adequate public services to all, the region’s population is spread too thin to experience robust cultural benefits, and the region is wasting some of the nation’s most fertile farmland for cheap, low-density single-family subdivisions and strip commercial development.

Before expanding out, the Cincinnati region should examine its available land resources and determine where infill is best suited. Vacant lots initially will make the most sense, but following that, Cincinnati’s hillsides should be seriously examined for smart development typologies like the ones found on the Greek islands that respect viewsheds, private property interests and the natural setting of the hillsides. This will not only make Cincinnati more economically and environmentally more sustainable, but it will make Cincinnati unique compared to other like cities across the United States that lack these creative hillside development opportunities.

Disclosure: Randy A. Simes worked for The Hillside Trust as a GIS Consultant from 2007 through 2009, and this editorial does not necessarily represent the views or values of The Hillside Trust.