I still remember when I learned to ride a bike. I lived in an apartment building that surrounded an inner courtyard. It was in this courtyard that my dad pushed me down one of the sides and let go, and it was in that moment that he let me go that I knew how to ride a bike, and I flew and flew and flew around that square until the sun had set and I was exhausted. My dad told me he was scared the whole time; I wasn’t.

Beyond the courtyard I went, as my family moved to a bigger home in the neighborhood across the street. My sister and I explored that neighborhood on our bikes, exhausting every corner, every cul-de-sac, until we reigned the land, but we were unsatisfied, and moved on to our old domain, the old apartments. We discovered that there were three identical buildings, all with their own unique courtyards– and ours was the best (It had a playground and a paved square around it and grass). And when we were done with that, we moved to the streets surrounding our elementary school, but found those to be dreary, devoid of life. We roamed around the gas station at the end of our residential zone, the college campus down the other way, and even to the library. We were not afraid of cars; we were not afraid of anything.

I remember re-learning how to ride a bike in Cincinnati, one and a half years ago in December 2023. My friend Bryce had convinced me to go on a bike ride with him from OTR, where I live, up the Central Parkway bike lane and into Camp Washington to the Cincinnati Sign Museum. I was terrified the whole time: Cars constantly wooshed past us in our narrow little lane, with large plastic toothpicks and some paint the only barriers between us and death. Turning left was confusing and terrifying– How do we stay in the bike lane? Do we need to get out and dart into traffic to get into the left lane? What if an oncoming car doesn’t see us while we’re in the intersection during the unprotected turn? It was cold but I was sweating. I was afraid to brake too hard but also afraid to go fast. I thought to myself that I would never ride a bike again.

Somewhere between childhood and adulthood, our sense of curiosity and exploration is overtaken by fear, but I think that only happens if we have forgotten how to explore and assess risk. Those two things are so important to childhood development, but how do we carry these skills into adulthood?

Now I ride my bike almost everywhere– I will cut even a five-minute walk down to a one-minute bike ride because I can. No bike lanes were built for me, but it took a kind and patient friend. It took the right environment and the right draws: A neighborhood with slow traffic, a single grocery store, a single library, a single coffee shop. And it took a willingness to be uncomfortable.

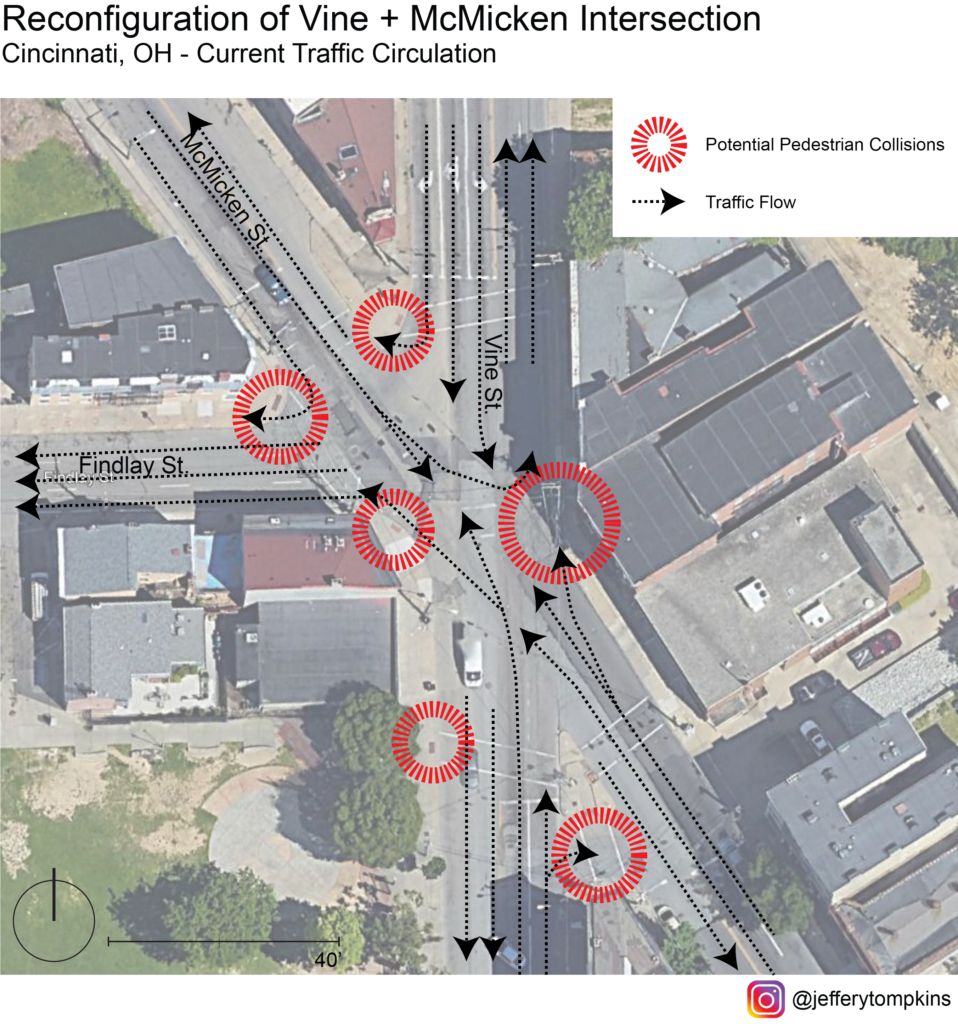

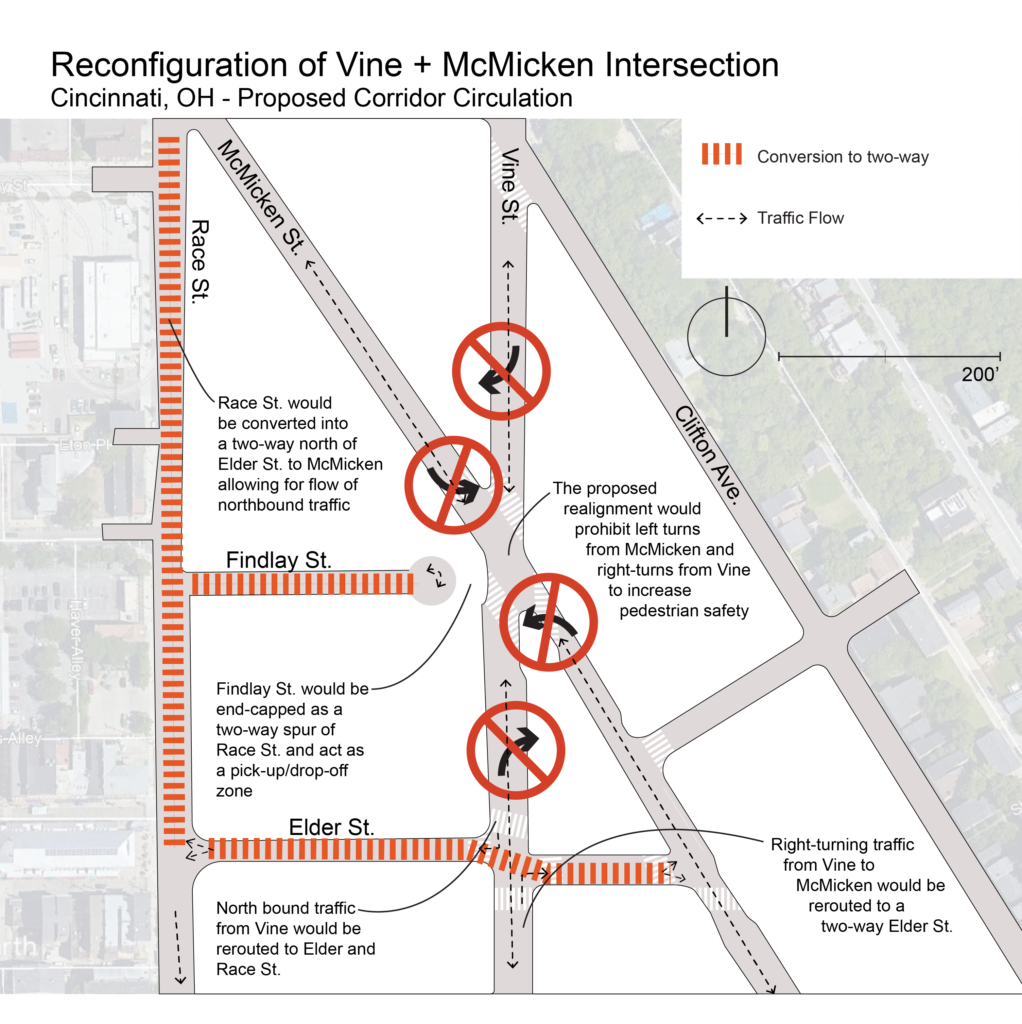

I don’t have all the solutions, but if we are dreaming of a car-free urban basin, why are we dreaming of spending millions on protected bike lanes when there will be nothing to protect them from? We shouldn’t just ask for a sliver of the road; we need to be asking for the whole damn thing. Not just for bikes, but for people to cross wherever they want, for people in wheelchairs to roll freely without being honked at or mowed down, for kids to run around and play and for picnics and barbecues and birthday parties to spill out.

Next Thursday, July 10 6-8pm, Rick Holt from the Early Childhood Mobility Coalition will be coming to YARD & CO (1542 Pleasant St.) to have a conversation about the intersection of infrastructure, culture, and individual actions in the effort to equip our next generation with the tools they need to safely navigate the world. My opinions are mine only, and I’d love to hear what Rick has to say!