April 7, 2001 is a day that has marked a changing point for Cincinnati and its people. On that day a white Cincinnati police officer shot, and killed, what was later discovered to be an unarmed 19-year-old black male. The shooting was the fifteenth deadly shooting of a black man, under the age of 40, since February 1995. Of those fifteen, three of the men did not possess any weapons. During that same time, four Cincinnati police officers were killed or wounded.

April 7, 2001 is a day that has marked a changing point for Cincinnati and its people. On that day a white Cincinnati police officer shot, and killed, what was later discovered to be an unarmed 19-year-old black male. The shooting was the fifteenth deadly shooting of a black man, under the age of 40, since February 1995. Of those fifteen, three of the men did not possess any weapons. During that same time, four Cincinnati police officers were killed or wounded.

The series of deadly interactions, between white police officers and black men, was heightened by the fact that none of the police officers were found guilty of any civil or criminal offenses. Following the death of Timothy Thomas, Cincinnati’s black community erupted into civil unrest for four days. Commonly known as the Cincinnati Race Riots, the civil unrest made international headlines and resulted in a hugely damaging economic boycott of the city.

Since that time much has changed. Federal investigators worked within the Cincinnati Police Department to ensure that changes were being made in the way the department conducted its business. In recent years the investigators determined that Cincinnati’s police force had made significant progress, and that its improved practices should serve as a national model of success.

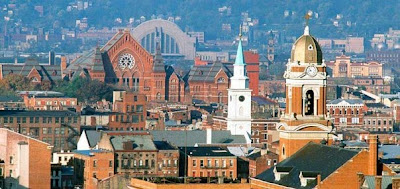

Over-the-Rhine, the epicenter of the civil unrest, is in the midst of one of the most dramatic urban transformations in the United States. Hundreds of new residents, dozens of new businesses, dramatically reduced crime and improved public infrastructure now define the historic neighborhood. More specifically, the dark alley where Timothy Thomas was shot and killed now houses upscale condominiums and a new streetscape.

Since April 2001, the city has also become a national center for racial dialog and civil rights issues. Since Cincinnati’s race riots and ensuing economic boycott the National Urban League, NAACP, National Baptist, Council for Black Studies, League of United Latin American Citizens and Civil Rights Game have all hosted, or will host, their national conventions in Cincinnati. Furthermore, the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center opened its doors on the banks of the Ohio River in 2004.

I personally remember April 2001. I remember hearing the police and fire sirens emanating from Western Hills Plaza. I remember the graphic scenes on television of protesters being shot with bean bag and rubber bullets. I remember the first night rioting broke out, and I remember the curfews implemented all over the region to prevent further unrest. I also remember just how close Cincinnati Mayor Charlie Luken was to calling in the National Guard.

At the time I was at the very beginning of a new stage in my life where I fell in love with Cincinnati. The riots were a cold splash of water to my face. I was hopeful for the new riverfront development and other developments proposed around the city. And with the riots, it all came crashing down.

The progress of Main Street in Over-the-Rhine was squashed overnight, the city got a negative reputation throughout the world, and the boycott epitomized by Bill Cosby’s comedy show cancellation seemed like the proverbial straw that would break Cincinnati’s back. Honestly, I was angry and did not understand what was happening in Cincinnati, but I feel now that it was for the best.

Cincinnati’s racial tensions of the late 90’s are not unique to the Queen City. And in fact, I believe that the tensions that boiled over into four days of unrest could very well happen in any number of cities around the United States.

The simple reality is that the structural segregation and disenfranchisement of America’s black population is not ancient history like so many would like to believe. Economic, political and social inequities still very often fall along racial lines in the United States, and those cities with a large white and black population shift have serious issues still to overcome.

The United States often has a bad perception around the rest of the world. Sometimes this is a reasonable perception, but other times it is not. While I feel that the United States has a long way to progress in many areas, I also feel that we air our dirty laundry so-to-speak. The airing of this dirty laundry allows us to make progress on complicated issues, and thus allows the U.S. to remain a beacon of freedom and hope for so many around the world and within our own borders.

What happened in Cincinnati in April 2001, I believe, was a similar action of airing dirty laundry. Since that time I feel that Cincinnati has made racial progress. Cincinnatians collectively received a splash of cold water to the face in April 2001, and we had to engage in difficult conversations and make difficult decisions to move on. Some of those conversations and decisions still need to be made, and some will never fully be resolved. But Cincinnati is now on a path to enlightenment that it would not have been without the civil unrest of April 2001 and the economic boycotts that followed.

What do you think…have race relations improved in Cincinnati since 2001? Were you around for the race riots, and if so, what was your experience? If you were not in Cincinnati at that time, what impression did you have of the city during the turmoil?

Cincinnati Police Officer photograph by Ronny Salerno.