Many of UrbanCincy’s readers have asked what it is you can do to help support the Cincinnati Streetcar and defeat the special interests that are once again trying to keep rail transit from Cincinnatians. Well, the time has come for you to get involved and get active.

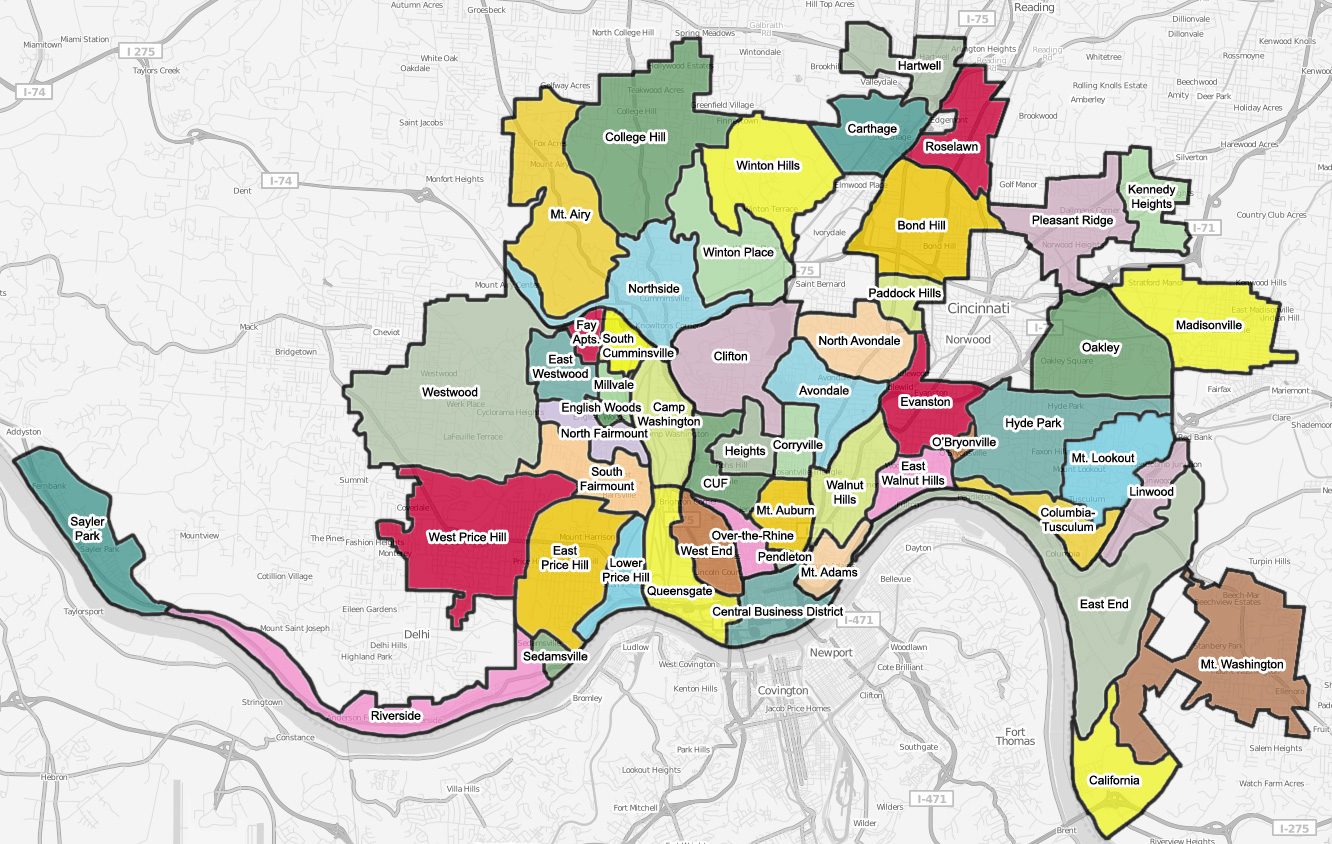

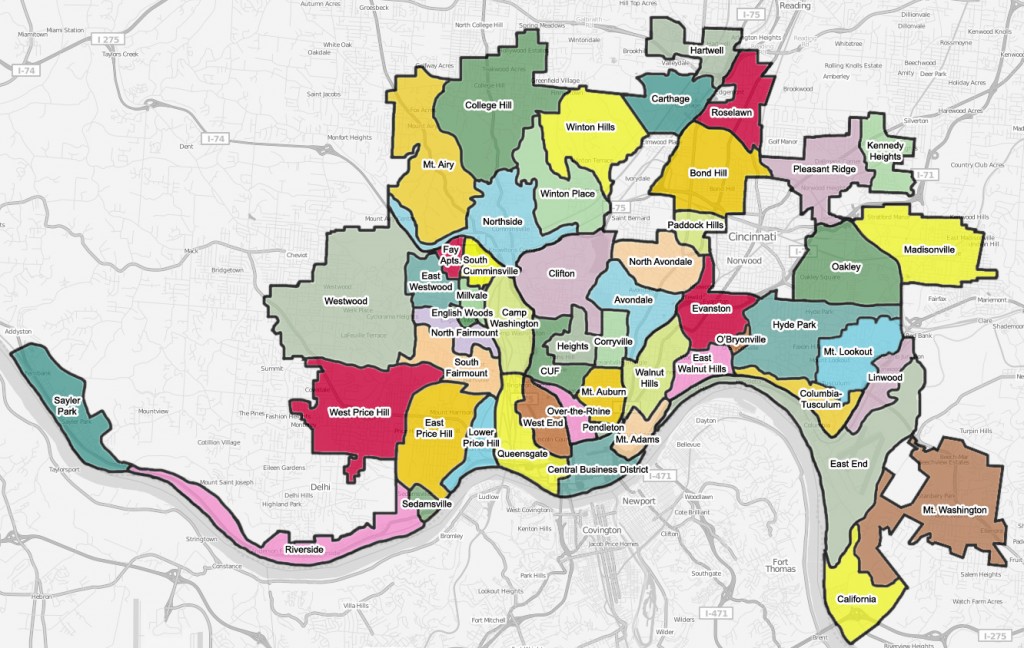

The first thing you can do is write an email to the State of Ohio encouraging them to continue their support of the state’s highest scoring transportation project. The special interests working to keep rail transit away from Cincinnati have made an aggressive push with the anti-transit Governor Kasich (R) to pull upwards of $50 million in state support from the project. The funding would largely help build the modern streetcar system from the riverfront to Uptown near the University of Cincinnati. Some of the money would also fund preliminary engineering work for phase two of the project which would send the streetcar further into Uptown.

You can contact the appropriate state officials by emailing TRAC@dot.state.oh.us (must email by Friday, February 11). Tell them why you support the Cincinnati Streetcar and be sure to remind them that this is the state’s highest scoring transportation project, by far, and that they should approve the $35 million in construction funding for “Cincinnati Streetcar Phase 1” and $1.8 million in preliminary engineering funding for the “Cincinnati Uptown Streetcar.”

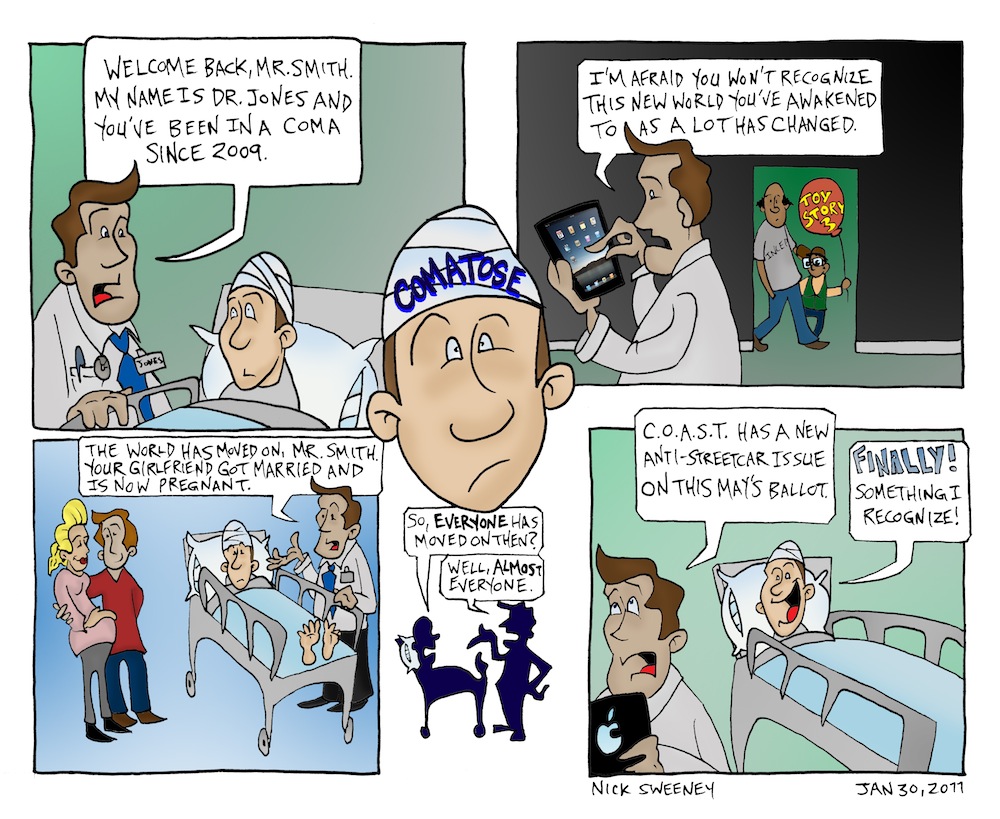

As COAST has returned to keep rail transit from Cincinnatians who voted their support for the project in November 2009, Cincinnatians for Progress has also returned to the scene to once again defeat those special interests. In 2009, CFP led a massive grassroots campaign that gathered approximately 10,000 Cincinnatians to make phone calls, canvass door-to-door throughout the city, organize fundraising efforts and run a get out the vote campaign.

The group is getting fired up for what may be a vote this May or November (Yes, in November when the city will be well underway building the streetcar system – approximately $50M worth of construction). If you would like to get involved, show up at their kickoff event to be held at Grammer’s (map) on Wednesday, February 16 from 6pm to 8pm.

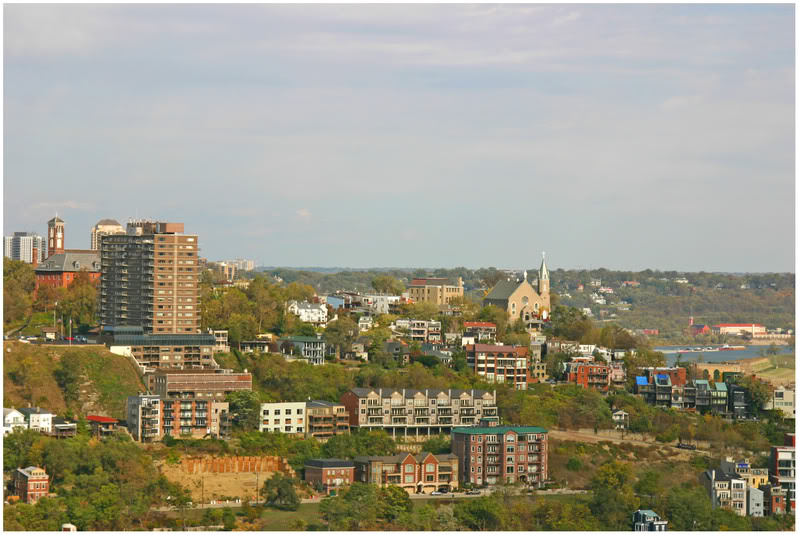

The Cincinnati Streetcar is projected to create 1,800 new construction jobs, generate thousands of new housing units, put people back to work, broaden the city’s tax base and continue the renaissance taking place in Cincinnati’s urban core.

At a recent press conference about the neighborhoods selected for the 2011 Neighborhood Enhancement Program, City Manager Milton Dohoney said the following.

I ran into a handful of people after the holidays who I guess had watched our struggles as we tried to deal with our budget in December, and they said uniformly, ‘Milton you look tired. Did you get any time off?’

Well, you can lay down if you’re tired, and you can lay down if you give up. But I work for the City of Cincinnati, Ohio and I’m not giving up. Our city is going places. We might be going kicking and screaming, but we’re going places.

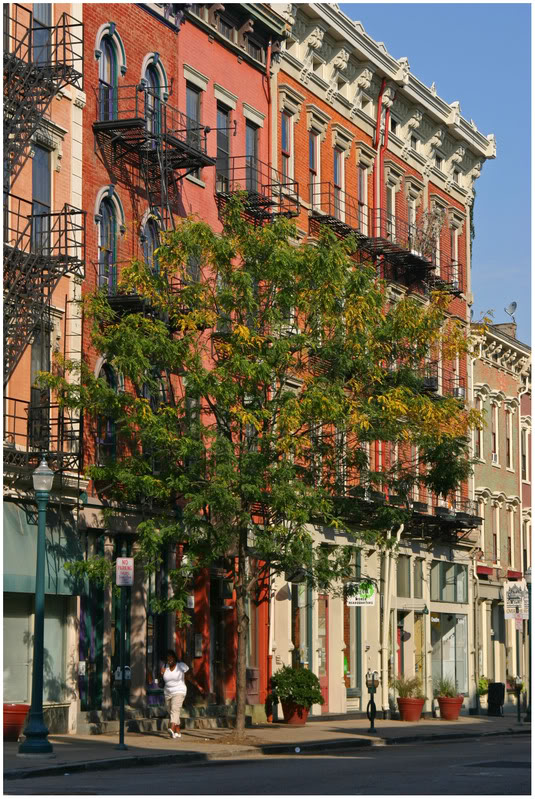

We are still feeling the recession, but in spite of that, we’re developing our waterfront, we’re breaking ground soon on a casino, we just did a project announcement for the Anna Louise Inn that will make a difference in people’s lives. LULAC is coming this year, the World Choir Games are coming next year, and yes we are still committed to buidlng a streetcar system. Music Hall is going to be redone, Washington Park is being redone and new people are coming to call Cincinnati home. We’re going to build some new houses in Bond Hill and we’re going to try to make a difference around Findlay Market in that area of Over-the-Rhine. We don’t have time to lay down.

We are not perfect, but you gotta love your city, and you gotta be willing to fight for it and advance it, and that’s what we’re about.

Like City Manager Dohoney expressed, stay passionate about what Cincinnati is, what it used to be, and what it can become. Support the Cincinnati Streetcar. Support Cincinnati.