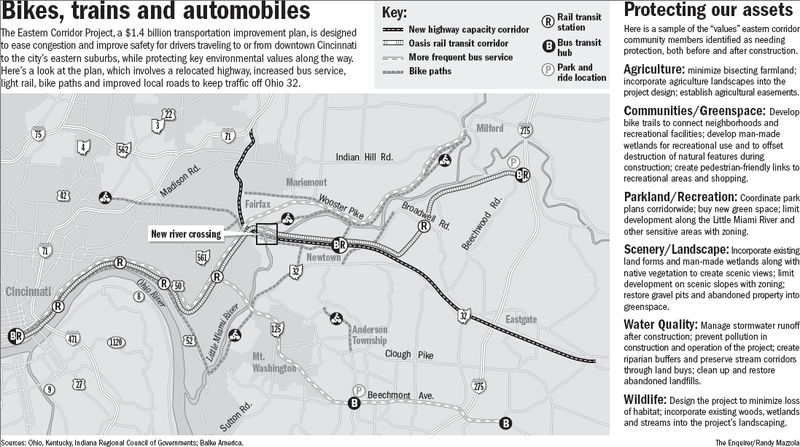

The Eastern Corridor project, a multi-modal highway and commuter rail plan for eastern Hamilton County, is back in the news. Two weeks ago Cincinnati City Council voted against endorsing a TIGER II grant application seeking funds for the plan’s 17-mile commuter rail component.

The local media predictably turned this event into another city-county dispute, and insinuated that the TIGER II grant might alone fund construction of the entire Milford commuter rail line, which in 2003 was estimated to cost $420 million. There is no possibility of this happening, as Milford commuter rail would need to be awarded approximately two-thirds of the entire $600 million sum to be dispersed nationwide by the TIGER II program.

The media also ignored the Eastern Corridor plan’s central feature – four miles of the Milford commuter rail line is planned to be built parallel to a new $500 million U.S. 32 expressway between Red Bank Road and a point east of Newtown. The 1990’s cost estimate for Milford commuter rail included the savings associated with building a combined highway and rail project, including a new shared eight-lane bridge over the Little Miami River. The cost of building the commuter line first without provision for the future highway has not been studied.

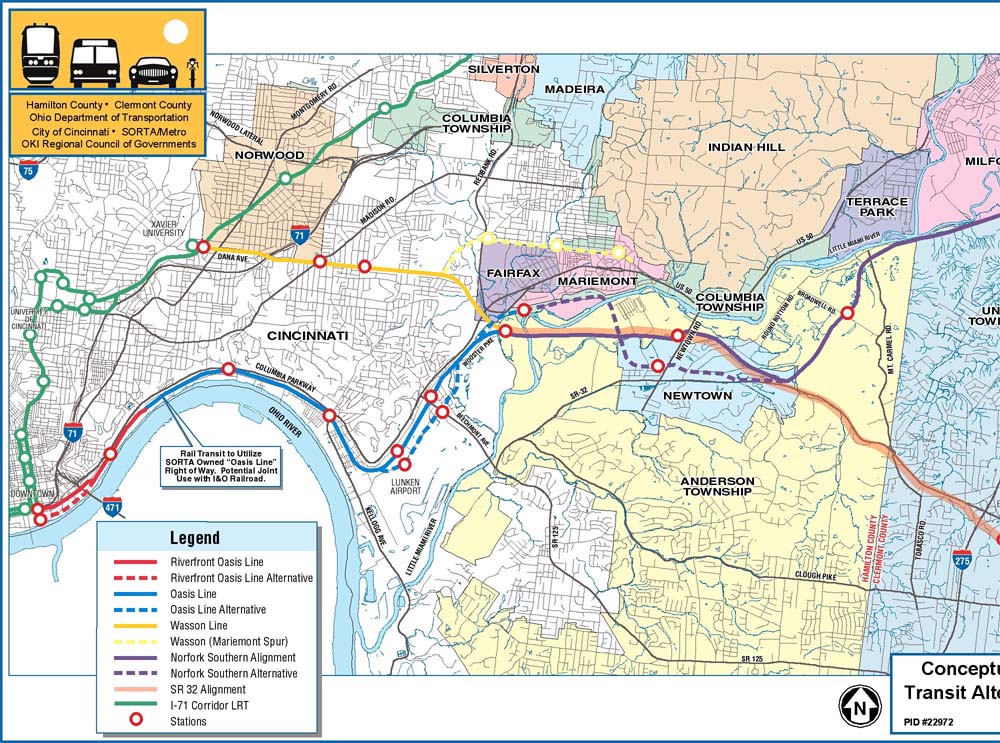

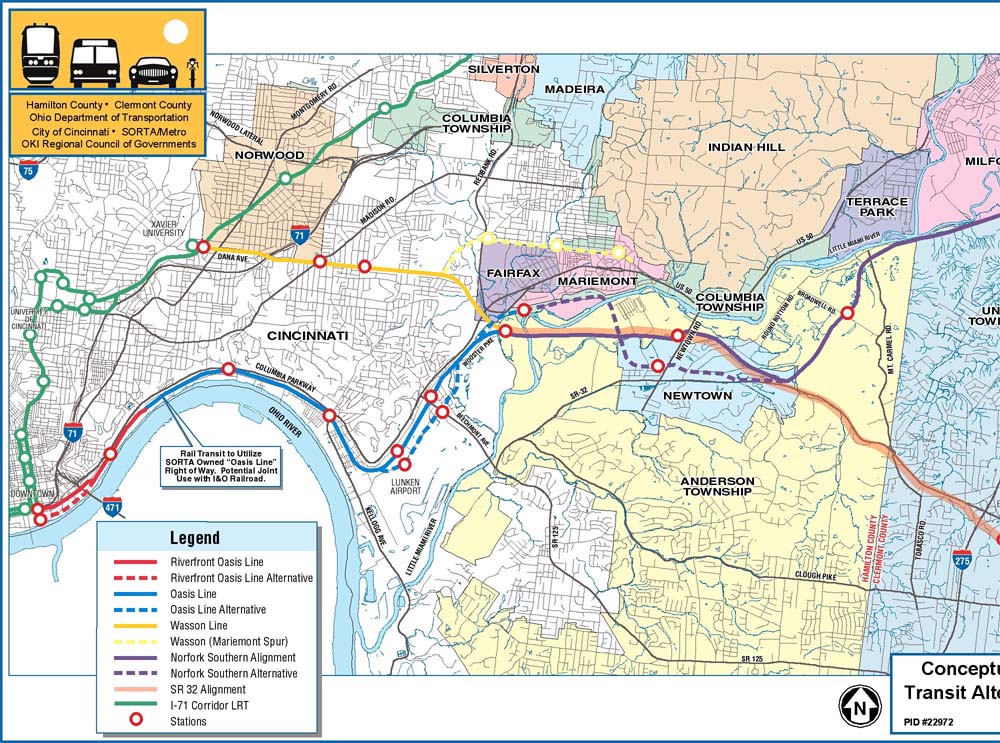

The Oasis Line

Between downtown Cincinnati and the proposed eight-lane bridge over the Little Miami River, the Milford commuter rail is planned to operate on an eight-mile stretch of track paralleling the Ohio River known as the “Oasis Line.” In the late 1980’s the L&N Bridge (now the Purple People Bridge) was closed to freight rail traffic, and thus ended the operation of large trains along the Oasis Line. Since that time, traffic has been limited to a handful of freight cars per week, and the Cincinnati Dinner Train on weekends.

At first glance it would appear that implementation of commuter rail service on the Oasis Line should require nothing more than the purchase of commuter trains and the construction of a connection between the end of active tracks and the Riverfront Transit Center. Unfortunately, the poor condition of the existing track limits traffic to a maximum twelve miles per hour, meaning all eight miles between the Montgomery Inn Boathouse and Red Bank Road must be rebuilt. It is also probable that the Riverfront Transit Center connection must be built at least partially through Bicentennial Commons at Sawyer Point. All of this new track must be heavy freight railroad track, not the smaller and less expensive track used by light rail trains and modern streetcars.

Even after this needed investment in new track, grade crossings will remain at a half-dozen locations along Riverside Drive and in Columbia Tusculum, where perfunctory horn blasts will disturb those residing in new condos along Riverside Drive, longtime residents atop Mt. Adams and East Walnut Hills, and will surely be audible across the river in Bellevue and Dayton.

Poor Station Locations

Residents of Riverside Drive will be able to hear the Milford commuter rail trains, but most will not live within easy walking distance of the line’s stations. Of five stations proposed along the Oasis Line, only one, Delta Avenue in historic Columbia Tusculum, can be considered auspicious. By contrast, little existing ridership or future development exists around either the proposed Theodore Berry Park or the Cincinnati Waterworks (downhill from Torrence Parkway) stations. Ridership at the proposed Lunken Airport station will be minimal, and the Beechmont Avenue station will primarily serve as a bus transfer point.

On top of this minimal ridership, Riverside Drive is already served by Metro’s #28 bus. If Milford commuter rail is built, this bus will still have to operate due to the infrequent service and long distances between stations along the Oasis Line. It is also likely that Metro’s #28X, which serves Mariemont and Terrace Park en route to Milford, will have to continue operations as well.

An alternative proposal that called for streetcar or light rail service between downtown and Lunken Airport could eliminate the need for the #28 bus route, thus freeing up resources for bus service elsewhere. In this scenario significant savings would be achieved due to the considerably lower track costs for streetcars and light rail when compared to the freight railroad track currently proposed for the Milford commuter rail. Additionally, the vehicles are much quieter because they are electrically powered, labor costs are halved because they require just one driver, and more stops could be placed at much closer intervals.

High Operations Costs

No funding source has been identified to cover the outrageous annual operating costs for Milford commuter rail. In 2004 its annual operations were estimated to be $18.9 million — a sum similar to the estimated annual operating cost of the proposed 250-mile 3C Corridor passenger rail service between Cincinnati, Columbus, and Cleveland.

The cause of these exorbitant operating costs is an alarming combination of mediocre ridership and high labor costs. A 2002 report projected approximately 6,000 weekday trips (3,000 commuters) along the Oasis Line at full build-out. For comparison, this ridership figure is roughly equivalent to Metro’s most popular bus routes. At the same time, the FTA requires a crew of two onboard all diesel commuter trains that operate on freight tracks, even for the small Diesel Multiple Units (DMUs) planned for the Eastern Corridor, due to safety regulations.

By comparison, the Cincinnati Streetcar as presently planned will cost approximately $128 million to construct, require $3 million per year to operate, and will attract similar or higher daily ridership with 15 fewer route miles of track. Last month, city officials were notified that the Cincinnati Streetcar was awarded a $25 million Urban Circulator grant. If an identical amount were hypothetically awarded to the Eastern Corridor project through TIGER II, it would cover so little of the much more expensive Milford commuter rail that no construction would even be able to take place. Meanwhile, an additional $25 million put towards the Cincinnati Streetcar could extend the line into Avondale or Walnut Hills immediately. This means a potential grant for the Milford commuter rail might sit in the county treasury for a decade or more, or through tricky accounting be integrated into the Eastern Corridor project’s highway funding.

The Wasson Line

An alternative rail route to eastern Hamilton County involves use of the Wasson Line, which joins the Oasis Line near Red Bank Road but travels a very different path between that point and downtown Cincinnati. This route is eight miles – the exact same distance as the Oasis Line – but promises much higher ridership and much lower operational costs.

Since all freight operations ceased on the Wasson Line in 2009, electric light rail vehicles staffed by a single driver can be used at considerable cost savings over diesel commuter trains needed on the Oasis Line. Proposed station locations at Xavier University, Montgomery Road, Edwards Road, and Paxton Avenue each promise higher initial ridership — in 2002 the Wasson Line was estimated to attract 20,000 daily riders, or triple that of Milford commuter rail.

Also different from the Oasis Line, redevelopment potential exists around all of the stations locations along the Wasson Line, but especially the 25-acre parallelogram-shaped parcel recently assembled by Xavier University between its campus and Montgomery Road. The abandoned Wasson Road Railroad bisects this property and converges with the similarly abandoned CL&N railroad at the present edge of Xavier’s campus. The particular junction played a major role in the 2002 MetroMoves regional rail plan due to the convergence of several regional lines on their way into downtown along shared Gilbert Avenue tracks.

The Edward Road station is another location superior to anything on the Oasis Line. It is located within walking distance of Hyde Park Square and the majority of the neighborhood’s population. The station would be placed adjacent to, or across the street from, Rookwood Commons shopping center, and just a three-minute walk from the undeveloped Rookwood Exchange site north of Edmondson Road.

The Wasson Line has decisive cost-benefit advantages over the Oasis Line, but it obviously cannot function without a connection between Xavier University and downtown. After completion of the Cincinnati Streetcar, construction of a light rail connection between these points should be a top priority. This section alone promises the highest per-mile transit ridership in the metro area, and reaching Xavier University allows construction of three light rail branches, on existing railroad right-of-way, as funds permit.

Regional Priorities

It is unclear why construction of the Eastern Corridor project is any kind of priority. Much of the expense will be borne by Hamilton County, but with parts of the highway and rail line traveling over the undevelopable Little Miami River flood plain, the new expressway and perhaps even the rail line will act to encourage sprawl in Clermont County. Even the terminal station for the Milford commuter rail will not be in Milford’s town center, where it would be within walking distance of several hundred residents, but rather two miles away at Milford Parkway, home to Wal-Mart, Target, and chain sports bars.

Anti-rail forces are fond of saying that rail advocates will support anything that runs on rails. But advocates of better public transportation know that funds for rail projects are scarce and must be applied where the best cost-benefit exists. Moreover, the best transit mode must be chosen for each route. In the case of inner-city rail to Cincinnati’s eastern suburbs, diesel commuter rail along the Oasis Line is not the best solution, but rather, light rail service along the Wasson Line is.