A newly released feasibility study, produced by KZF Design, finds that construction of the 6.5-mile Wasson Way Trail would cost anywhere from $7.5 million for just a trail to $36 million for both a light rail line and trail totally separated from one another.

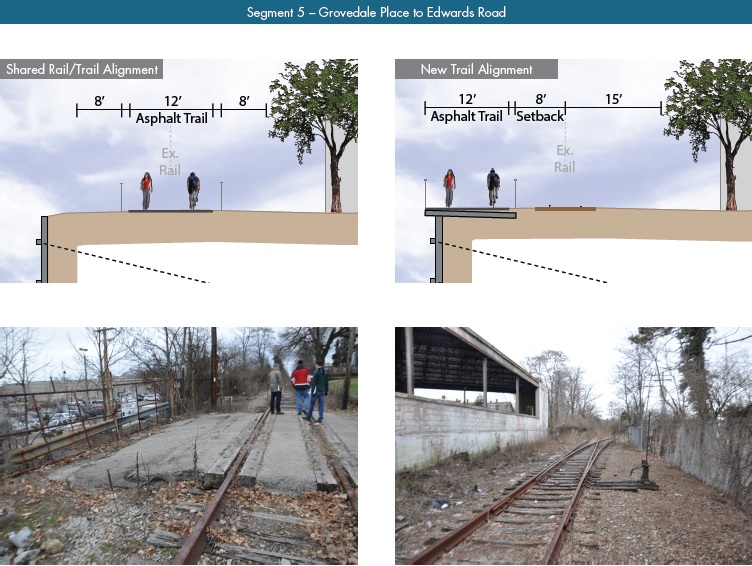

The cost estimates vary so much due to the three potential design options studied. The lowest cost alternative looked at placing a 12-foot-wide trail along the entire existing rail alignment. This, however, would make the inclusion of a future light rail line extremely difficult.

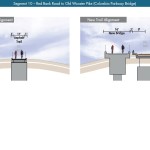

The most expensive alternative would construct an entire new trail alignment that does not interfere with any existing rail right-of-way. This would include the construction of several new bridges and completely preserve the ability to easily construct the long-planned light rail line adjacent to the new trail.

Alternative B, which was recommended by KZF and priced at $11.2 million, was a bit of a hybrid. It would include a 12-foot-wide trail offset from the existing rail alignment, but utilize existing rail right-of-way at pinch points along the corridor.

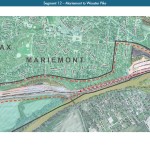

The 45-page study is the first detailed look at the corridor, which has been hotly debated and discussed over recent years. Much of the controversy has surrounded whether or not both light rail and a trail can be accommodated. KZF’s findings appear to show that much of the corridor could in fact accommodate both, but that some segments may prove to be difficult, albeit feasible.

If project supporters are able to advance the trail plan, KZF estimates that it would connect eight city neighborhoods and approximately 100,000 residents with an overall network of more than 100 miles of trail facilities.

“It is hard to build in the urban core, and to find an intact corridor ripe for development is a unique thing,” explained Eric Oberg, Manager at the Midwest Rails to Trails Conservancy. “If this is done right, this can be the best urban trail in the state of Ohio. I have no doubt.”

Some of the most difficult segments of the corridor are the nine existing bridges where the right-of-way is extremely limited. If both light rail and trail facilities are to traverse this corridor together, additional spans will be needed in order to have safe co-operation.

In addition to introducing what may become the region’s best urban trail and light rail corridor, some proponents also see it as an opportunity to fix other problems along the route. Most notably that includes the congested and confusing intersection of Madison, Edwards and Wasson Roads near Rookwood Pavilion.

While the newly released feasibility study offers the most detailed analysis of this corridor to date, the City of Cincinnati has yet to close on its purchase of the former freight rail line from Norfolk Southern.

City officials are reportedly in negotiations with Norfolk Southern now, and have made an initial offer of $2 million. In April, Mayor Cranley’s Administration also allocated $200,000 to the project.