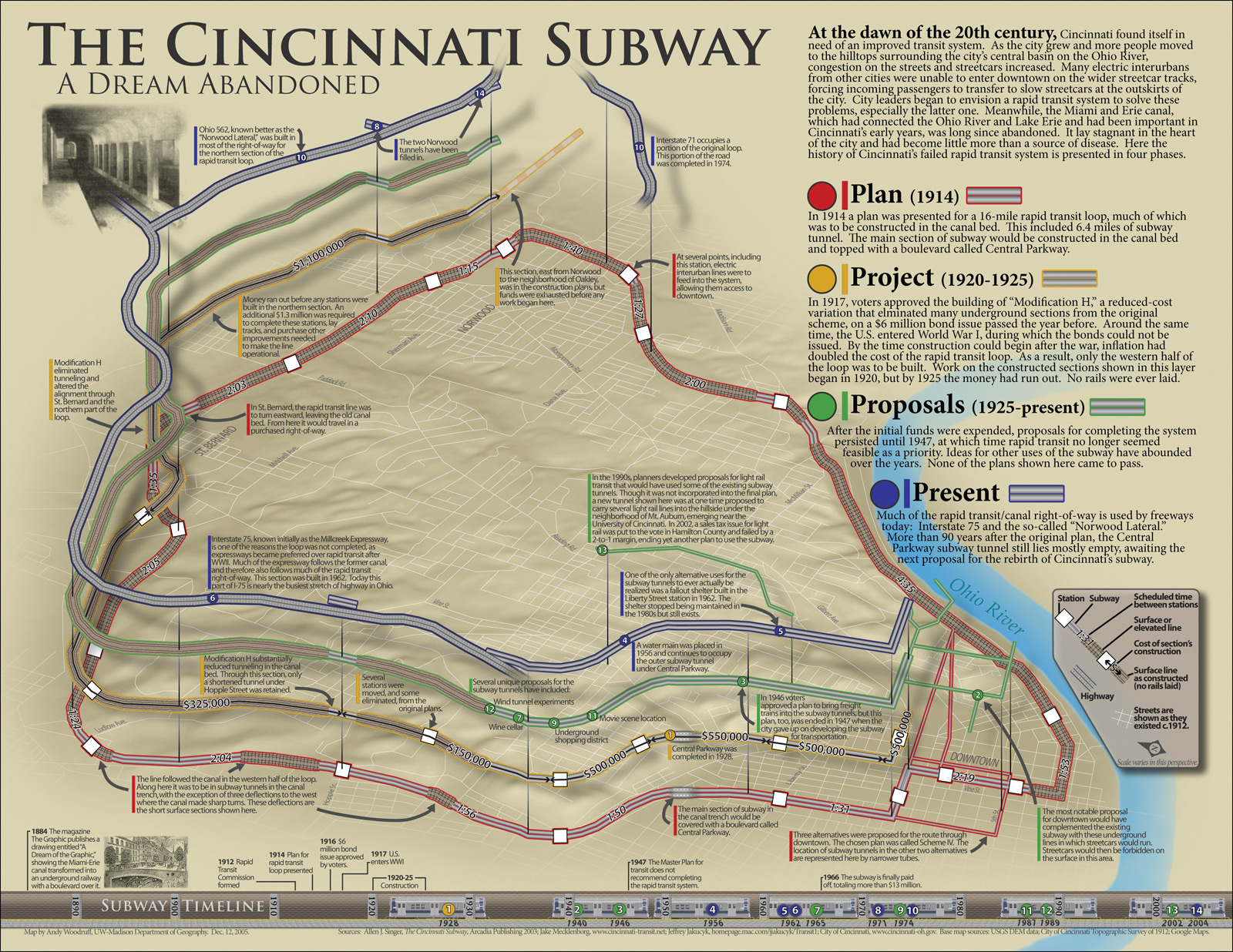

As bicycling continues to grow in popularity in Cincinnati, the city has built out more and more bike infrastructure. These new accommodations, including the new protected bike lanes on Central Parkway, are making it safer for bicyclists and are attracting more riders.

The Central Parkway Cycle Track provides a new protected, on-street route for bike travel between downtown and neighborhoods to the north, including Northside, Camp Washington and Clifton.

City transportation planners say that there has been apprehension for many cyclists to ride in high volumes of speedy traffic. This is particularly true for Central Parkway, which officials say was often avoided by many due to the intimidating nature of the street’s design that favored fast-moving automobiles. Since the opening of the Central Parkway Cycle Track, however, city officials say that there has been a substantial increased in bike traffic there.

Bike advocacy groups consider the project to be the first of its kind in Ohio. It stretches approximately about two miles from Elm Street at the edge of downtown to Marshall Avenue in Camp Washington.

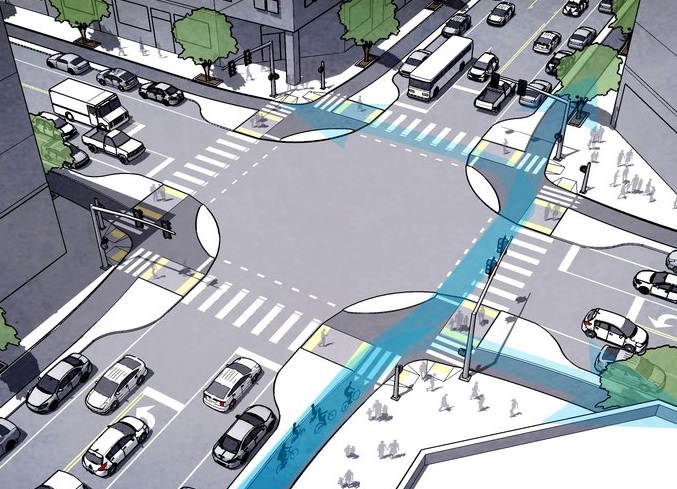

The protected lanes differ from other bike lanes recently built in other locations around the city in that they are separated from moving traffic by a painted median several feet wide. To further delineate the two modes of traffic, the median also includes flexible plastic bollards spaced about 15 to 20 feet apart. This separation then pushes on-street parking out away from the curb.

At one point along the parkway, close to Ravine Street, the southbound lane leaves the street to run on a newly constructed path along the sidewalk for several hundred feet in order to allow 24-hour curbside parking. The off-street path is made of concrete dyed in a color intended to resemble brick.

During the heated debate over this design change, many expressed concern that construction of the new pavement could result in the loss of a large number of trees. Fortunately, due to careful planning and design coordination between city planners and representatives from Cincinnati Parks, who have oversight of the city’s landscaped parkways, they were able to preserve many of the trees in this area. According to city officials, only two trees in total were lost due to the lane.

Transportation officials are now working to link these protected bike lanes along Central Parkway with future bike routes along Martin Luther King Drive and on the reconstructed Western Hills Viaduct.

Furthermore, after work on the Interstate 75 reconstruction project near Hopple Street is complete, planners will consider the extension of the protected lanes north to Ludlow Avenue. But first, Mel McVay, senior planner at Cincinnati’s Department of Transportation & Engineering, told UrbanCincy that the first segment needs to be examined first, and additional community feedback will be necessary.

“We need to see how successful the first section is,” McVay explained. “It [the second phase] will depend on what the community wants.”

EDITORIAL NOTE: All 25 photos were taken by Eric Anspach for UrbanCincy in late September 2014.