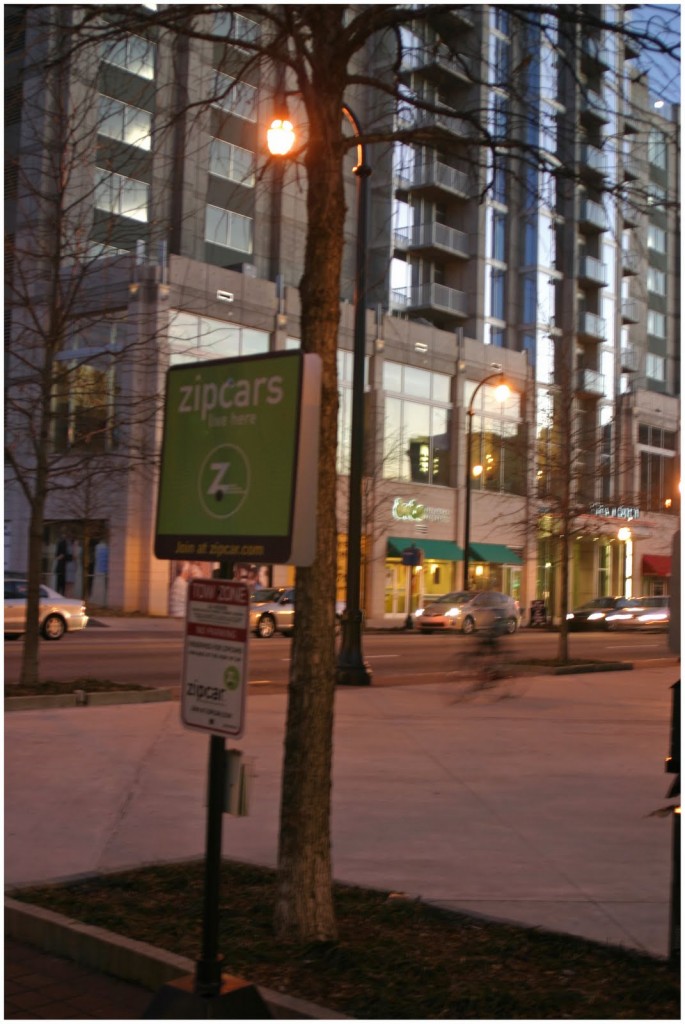

A group of young leaders in Cincinnati believe it is long past time for the city to have a carsharing program of its own. The group of individuals make up the Transportation Committee of the Young Professionals Kitchen Cabinet (YPKC) which provides policy ideas and suggestions to Mayor Mallory that will help to both attract and retain young talent.

A group of young leaders in Cincinnati believe it is long past time for the city to have a carsharing program of its own. The group of individuals make up the Transportation Committee of the Young Professionals Kitchen Cabinet (YPKC) which provides policy ideas and suggestions to Mayor Mallory that will help to both attract and retain young talent.

The idea for carsharing comes from a growing number of people either going car-free or car-light. What makes the issue particularly relevant to the YPKC is the fact that young people seem to be leading that trend. Nationally, the percentage of 16-year-old drivers with licenses has decreased from 41 percent in 1996 to 29.8 percent in 2006, and in Ohio that number has dropped five percent since 2000 alone according to the state Department of Public Safety and U.S. Census Bureau.

“This isn’t a very controversial topic, and many cities our size that don’t have transportation options beyond buses are able to make carsharing work,” said Chad Schaser, YPKC Transportation Committee member. “What they have realized is that you can create a successful program by starting around universities and the center city, where the number of people owning automobiles is historically lower, then work your way out from there.”

According to Schaser, their push for a carsharing program in Cincinnati could come in a number of forms. One option, he says, is to attract an existing carsharing service like Zipcars to the region.

“We first started working on the idea of a carsharing program in 2008 and really began in earnest this year,” Schaser explained. “Through our research we looked at locally run programs in Cleveland and Pittsburgh and we wanted to figure out how to recruit a carsharing program to Cincinnati, but we did not get a great response.”

Once the group discovered the likelihood of attracting a major carsharing provider to Cincinnati was low, they decided to shift their attention to figure out how to start a local carsharing program similar to those in Cleveland and Pittsburgh. The group then took six months to study the feasibility and put numbers together that would help generate a basic business plan.

The draft business plan put together by the group says that an initial 20-car fleet with some 500 members makes operations quite feasible, but Schaser says the real trick is coming up with the initial capital needed which they project to be around $250,000.

“If we can make this sustainable then there’s not going to be much opposition. Our goal is to make a program work here that won’t require taxpayer or major funding to make it happen.”

One way to get things going, Schaser says, is to get large employers to sign on as a charter member thus providing an upfront base of users. Once such member could be the City of Cincinnati which could be able to save millions of dollars annually by ridding itself of vehicle ownership and maintenance. After selling 329 vehicles, the City of Philadelphia was able to save $6 million through lower insurance costs, less use, and less abuse in just three years with its partnership with Philly CarShare.

But beyond landing an initial charter member, the committee feels like there will be some work in making Cincinnati a better place to live either car-free or car-light.

“In Cincinnati people are addicted to their automobiles,” exclaimed Schaser. “We think that the Cincinnati Streetcar will be well-used, and marrying a carsharing program with our existing and future transit options will help create a lesser dependence on cars.”

Right now the committee is conducting an online survey to gauge initial interest levels in Cincinnati. The survey can be taken through December 1, 2010. At that point Schaser says that the group hopes to take the idea and preliminary business plan to City officials for further development.