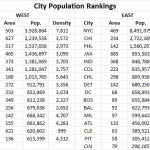

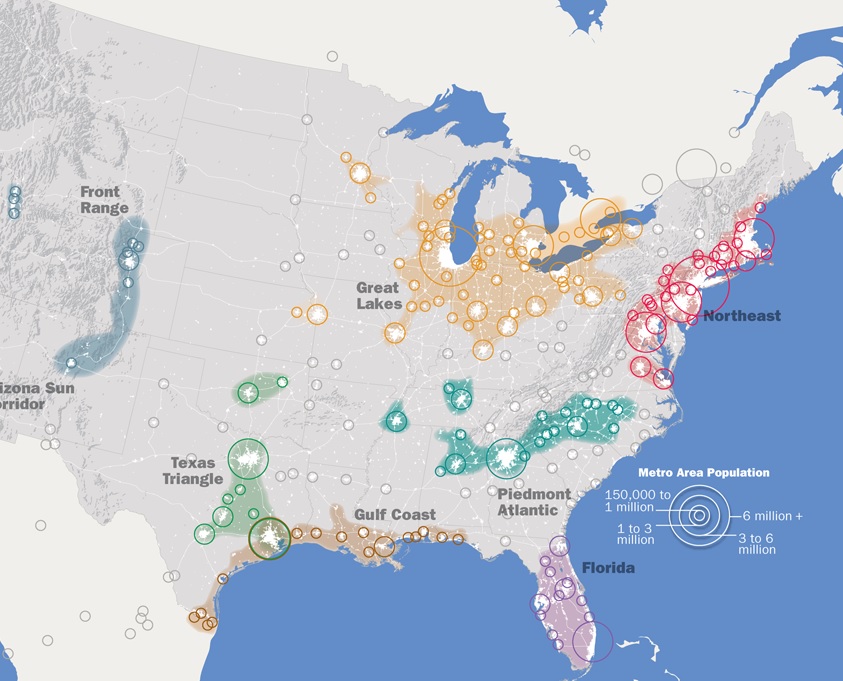

Following the release of the U.S. Census Bureau’s updated population numbers for American cities, much has been made about the urban rise of the west. Even the Census Bureau itself touted the growing number of cities with more than 1 million people – the vast majority of which are located west of the Mississippi River.

These numbers can be misleading, and often don’t even pass the smell test.

Is Jacksonville, for example, really a bigger city than Detroit, Washington DC, Atlanta and Boston? Or out west, would most people actually consider Phoenix to be a larger city than San Francisco, Seattle, Denver or San Diego? Of course not.

In both scenarios, however, that is precisely the case. That is because the municipal boundaries for Jacksonville (885 square miles) and Phoenix (517 square miles) are disproportionately large compared to the population of their city. Closer to home the same is true for Columbus (223 square miles), Indianapolis (368 square miles) and Charlotte (298 square miles) – all of which skew the average population density for cities east of the Mississippi downward due to their huge municipal footprints.

If you were to simply pick-up a daily newspaper and read the listing of America’s most populated cities, you would not get this full perspective and perhaps be misled to think that Columbus is the biggest city in Ohio, or that Indianapolis is the fifth largest city east of the Mississippi River.

Using this same practice, some might consider Cincinnati to be a small city that doesn’t even crack the top 30 in the United States.

Of course, we know all of this is skewed by all sorts of factors. Some cities sit on state or county lines, others follow historical boundaries from hundreds of years ago that have never changed, while other are granted more liberal annexation capabilities. In short, it’s politics.

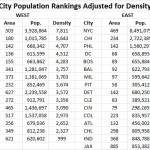

Now if we were to look at America’s 30 most populous cities again, but rank them by population density instead of overall population, the picture would change rather dramatically. Most cities in the west fall considerably, while older cities in the east would rise. The outliers that have artificially inflated their boundaries over the years also fall into a more normalized position on the chart.

While Cincinnati is not in the top 30 in terms of population, we considered it anyways since this is UrbanCincy after all. After adjusting for population density, Cincinnati would vault all the way to the 16th “biggest” city in America, just behind Denver and ahead of Dallas. This is also more in line with Cincinnati’s metropolitan population ranking that falls within the top 30 in America.

Those cities in this analysis that are in the east have an average population density, outliers included, of 6,579 people per square mile, while those in the west, come in at 3,804 people per square mile.

If outliers like Jacksonville actually were as large as they project, and followed the average population density for the region, it would need to add close to 5 million people. Likewise, Indianapolis would need to add around 1.6 million people and Charlotte 1.1 million. Local politics and market conditions in each of these cities will never allow for this many new people to move within city limits.

The Washington Post is correct in that the west is getting more populated and urbanizing at a fast pace, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves. The most populated cities in the west would only be average, at best, in the east if they were judged by population density instead.

Now, factoring for population-weighted density would be an entirely different ballgame.