Nearly seven years after phase one of the $84 million Village at Stetson Square development opened, developers stood with city and neighborhood leaders in Corryville this morning to celebrate the groundbreaking of the project’s next phase.

Once fully complete, phase two will include a total of 18 condominiums in four different buildings, with prices ranging from $200,000 to $275,000.

In order to help compliment the development, the City of Cincinnati will be contributing $340,000 towards infrastructure improvements in the immediate area. The development team expects the first residents to begin moving in by August 2013.

The Stetson Square development got off to a fast start with its large first phase. Until phase two designs were revealed in May 2012, the second and third remaining phases of work had been left undeveloped and up in the air with regards to when they would get started.

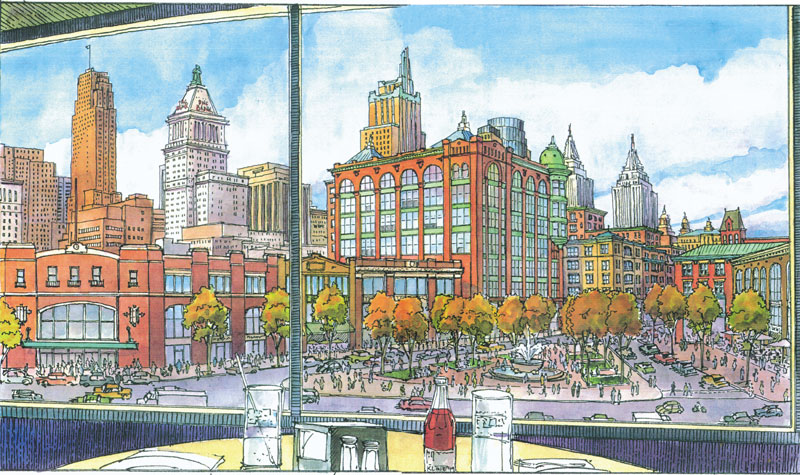

The second phase of work at Stetson Square kicked off today – nearly 13 years after the original plan was developed for the project in 2000. Image provided.

“We are very proud of Stetson Square and what it has contributed to the Corryville neighborhood and Uptown area,” explained Jamie Humes, Vice President, Great Traditions Land & Development. “It is an exciting, transformative time for people to live within the City of Cincinnati.”

In addition to adding new owner-occupied housing units to the Corryville neighborhood near the booming medical research block, the developers are also pursuing Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certification.

In December 2012, Cincinnati City Council passed new measures overseeing the tax incentives distributed for LEED-certified project.

But while phase two is finally getting started, the prominently located phase three has yet to have its future defined. When asked about the future of phase three, Humes stated that there is no definitive plan or use for it yet.

“Our perspective is that the marketplace will ultimately determine what the best land use and timing for development will be,” Humes clarified. “Corryville Community Development Corporation (CCDC) will then make the decision on how to proceed.”

Phase two of Stetson Square is considerably smaller than phase one, and will welcome its first residents by fall 2013. Rendering provided.

In 2006, Great Traditions informed UrbanCincy that phase three would eventually result in either apartments or condominiums, with a preference for additional owner-occupied units if the market would allow. The undeveloped lot sits at the corner of Martin Luther King Drive and Eden Avenue, and the CCDC currently retains ownership of the property.

Great Traditions touts that Stetson Square has 100% of its 79,000 square feet of office space and 92% of its 15,000 square feet of retail space occupied, more than 400 people living within the first phase’s 53 condominiums and 205 apartments.

The extended period it has taken to build out the development may be attributable to a sluggish economy, or even the fact that Stetson Square was Great Tradition’s first major foray into the urban real estate market.

“When Stetson Square was originally conceived, it was designed not only to be a great project, but also to serve as a catalyst for the revitalization of Corryville,” Humes told UrbanCincy. “To have the opportunity to translate this concept into an urban context with Stetson Square has been a natural and exciting progression for our company.”