According to the most recent numbers from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, there are just over seven thousand homeless people in Cincinnati. To be specific, there were 7,062 people either on the street or in a shelter in 2013.

This number can be a bit misleading since it does not include the many more people who have recently lost their home and are now staying with a family member or friend, or are unable to be counted at all.

The way in which local organizations are handling this situation is different today than it was decades ago. In the past the trend was to provide what experts refer to as site-based units. This has changed over the years to a model more akin to Section 8 housing vouchers, where subsidies are provided for people to go find housing out on the open market.

According to the Strategies to End Homelessness, approximately 97% of the 3,300 people in permanent housing in Cincinnati are in these scattered sites. Part of the reason for the change is due to changing funding priorities, while another large factor is that many people reject the idea of having supportive housing built in their neighborhood.

This has caused problems for local leaders who view the Homeless to Homes plan, which includes the construction of five new shelters, as part of a long-term solution. While the shelters are new and improved, they also typically include an overall reduction in total units provided. So with the total number of units and the number of homeless remaining constant, some are wondering what the ultimate solution is.

Salt Lake City has recently received national praise for their homelessness program where they simply have built and provided housing units for every homeless person in their community. It is a nod to past techniques, but one that appears to be getting results.

While it has received the attention, not everyone is convinced that Salt Lake City’s approach is all that unique, or all that comprehensive.

“It’s about giving people housing,” Kevin Finn, President and CEO of Strategies to End Homelessness, told UrbanCincy. “If homelessness is the problem, then providing housing is the solution.”

The problem, Finn continued, is that the vast majority of the funds that are provided by the Federal government has strings attached and almost never allows for prevention programs. And with homelessness typically being what Finn calls a short-term crisis, a strong investment in prevention might actually be more effective and economically sustainable.

“Somewhere around 80% of people who become homeless end up getting out of homelessness on their own,” noted Finn. “Unfortunately, we seem to be discouraged from even using the money that could be used for prevention on prevention.”

While Finn acknowledges that simply providing housing to those who truly need it is more effective than anything else, he also is quick to note that taking preventative measures can be far more cost-effective.

In Hamilton County, for example, it costs approximately $3,300 per year to provide supportive housing to someone. At the same time, it costs around $1,300 per year to shelter a person on a temporary basis, and just $1,100 annually to prevent someone from becoming homeless.

“I would agree that Salt Lake City has the right model for those that are homeless, but I would say that prevention is even more effective than that,” Finn emphasized. “The real challenge is to figure out what the right solution is for each individual person.”

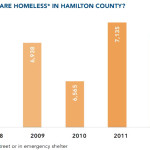

Further complicating the prevention approach is its inconsistent funding levels from the Federal government. According to Strategies to End Homelessness, virtually no funding was provided for prevention prior to 2009, but then the American Recovery & Reinvestment Act infused local agencies with around $2.2 million annually over the next three years. At its peak in 2011, it resulted in the prevention of 2,800 people from becoming homeless.

When the stimulus program wound down, those funds went away with it; and those numbers have been in rapid decline ever since. Such inconsistencies make developing long-term plans and strategies next to impossible.

“The issue we struggle with is trying to reduce homelessness when the landscape of the resources is constantly changing,” said Finn. “From 2012 to 2013 homelessness increased in Hamilton County; but it was less than 1%, and considering our resources had been decimated it was a bit of a moral victory.”

Beyond just the funding issues, understanding the problem and recognizing the actual need for each person could yield even greater performance and savings.

First and foremost, Finn says the goal should be to determine who is close to homelessness, but can be prevented from reaching it. From there he says that it is important to figure out who has recently become homeless, and what level of assistance they need – short- or long-term. Not doing so could create the risk of providing the funds for someone to have long-term support, even though short-term support is all that is needed.

In order to tackle each case appropriately, local leaders are developing an early stage approach that is in line with nationally recognized assessment process for determining these details that can often be difficult to uncover.

Further assisting those efforts are the already established programs operating county-wide, including the Central Access Point hotline that allows for people to call and give notification that they are at risk.

Even with all of the challenges, Finn remains optimistic about the future. The City of Cincinnati has recently increased its amount of funding for human services, and has designated reducing homelessness as a priority for those funds. In addition to that, the United Way of Greater Cincinnati is now providing $150,000 per year for prevention efforts.

New data is scheduled to be released in the near future with updated figures on the region’s homeless population. While it is not yet public what those numbers are, it is expected that they will be along a similar trajectory as recent years. The hope, however, is that this trajectory starts to change sooner rather than later.

“Ultimately if we can prevent people from ever coming in, then we can save a lot of money and save that household the trauma of becoming homeless,” Finn concluded.