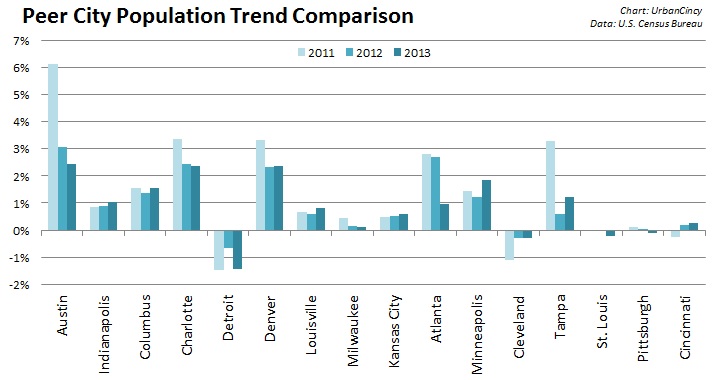

Like many cities across the United States, the City of Cincinnati is gentrifying, but it is doing so at a faster rate than most of its Midwestern peers – ranking fourth only behind Chicago, Minneapolis and St. Louis. When compared with the primary city in each of the nation’s 55 most populated metropolitan areas, Cincinnati is in the middle of the pack. Those cities that are gentrifying most quickly are located in the Northeast and along the West Coast.

The information comes from a new report published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, which also dove into the financial implications of what is often generally considered a bad thing.

Gentrification is generally understood as the rise of home prices or rents in a particular neighborhood. In Cincinnati this has most vigorously been discussed as it relates to the transformation in Over-the-Rhine from what was one of the city’s poorest neighborhoods, to now being one of its trendiest.

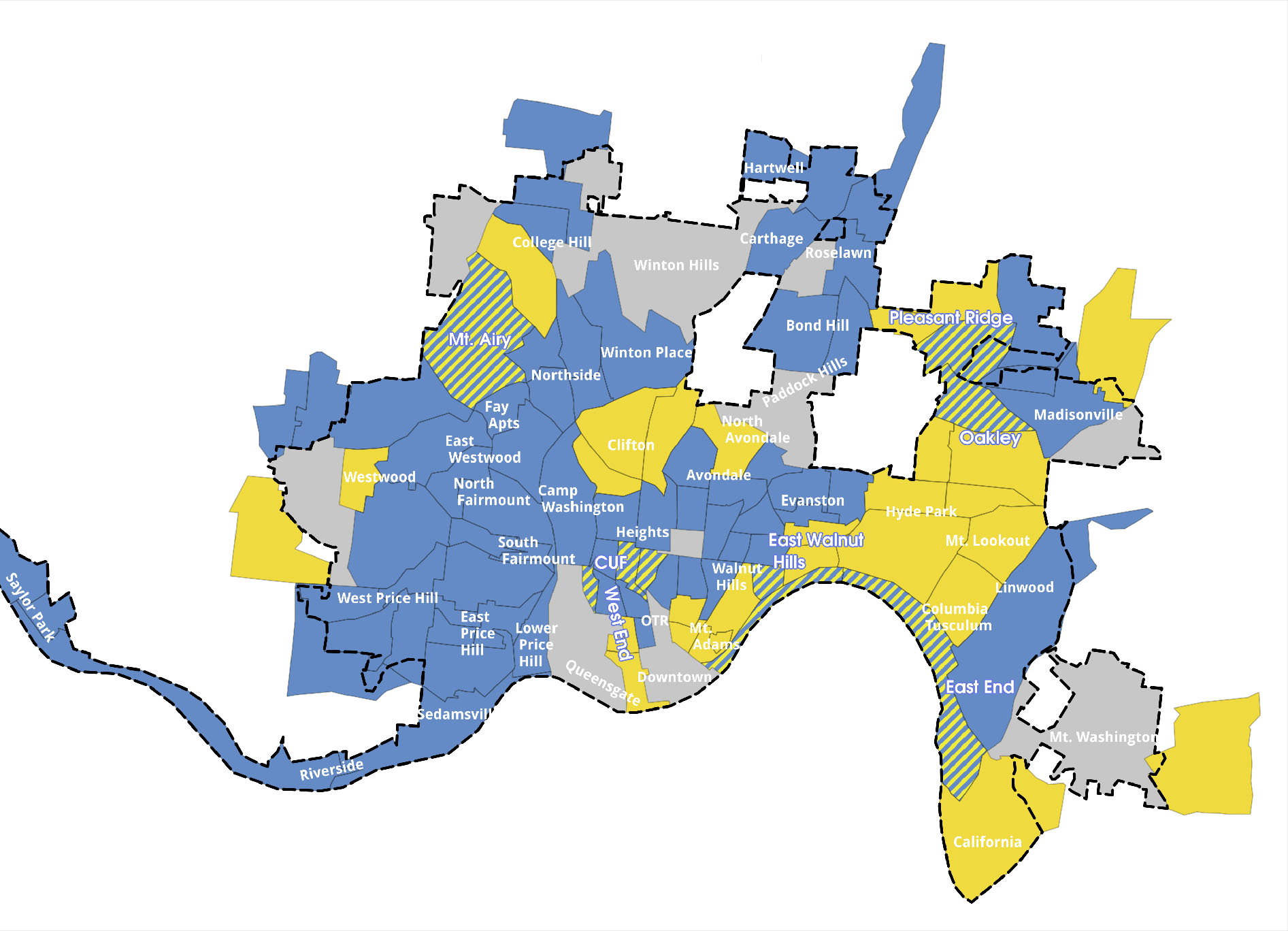

The Clifton Heights neighborhood, which continues to see a surge of private real estate investment, was found to be one of several Cincinnati neighborhoods that gentrified between 2000 and 2007. Photograph by Randy Simes for UrbanCincy.

“Gentrification is sometimes viewed as a bad thing. People claim that it is detrimental to the original residents of the gentrifying neighborhood,” stated Daniel Hartley, a research economist focusing on urban and regional economics and labor economics for the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. “However, a look at the data suggests that gentrification is actually beneficial to the financial health of the original residents.”

What Hartley’s research found is that credit scores for those living in a neighborhood that gentrified between 2000 and 2007 were about eight points higher than those people living in a low-price neighborhood that did not gentrify. He also discovered that delinquency rates, as represented by a share of people with an account 90 or more days past due, fell by two points in gentrifying neighborhoods relative to other low-price neighborhoods during the same period.

Some, however, caution against drawing conclusions about the data presented in Hartley’s report.

“I don’t see any reason why gentrification would affect the credit scores of existing residents – those who lived in the neighborhood prior to gentrification occurring,” commented Dr. David Varady, a professor specializing in housing policy at the University of Cincinnati’s School of Planning. “It was my impression that banks and other financial institutions were not supposed to take the neighborhood into account but rely on the family’s financial characteristics.”

The practice Dr. Varady describes of banks and financial institutions taking neighborhoods into account is called redlining. It is a practice that was rebuffed by the Fair Housing Act of 1968 and the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977, but some believe the practice persists in more abstract forms today.

One of the biggest concerns shared by those worried about the gentrification of neighborhoods is that it is particularly those that rent, rather than own, who are affected most. This too, however, is challenged by Hartley’s research.

“Mortgage-holding residents are associated with about the same increase in credit scores in gentrifying neighborhoods as non-mortgage-holding residents,” Hartley explained. “This result suggests that renters in gentrifying neighborhoods benefit by about the same degree as homeowners.”

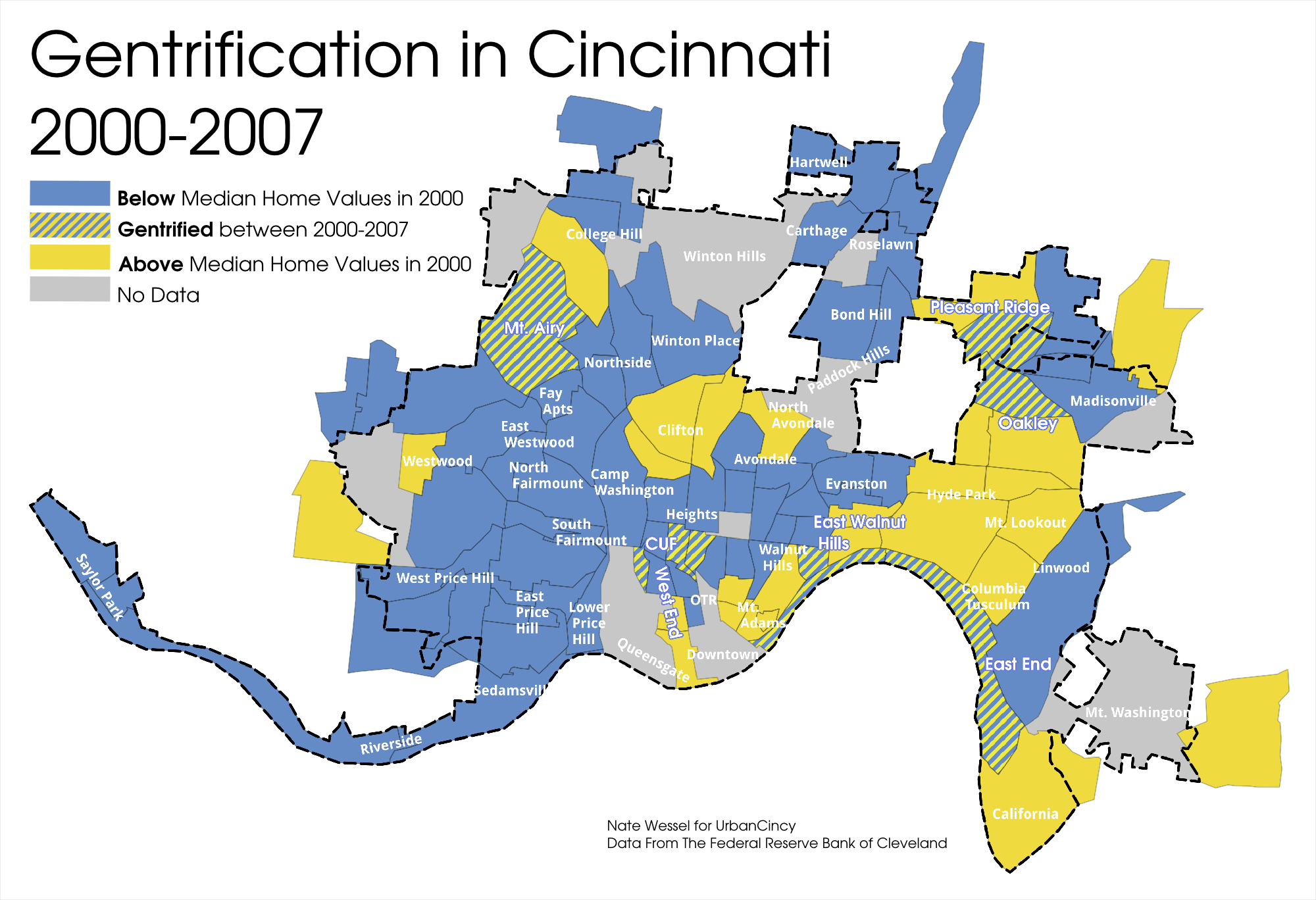

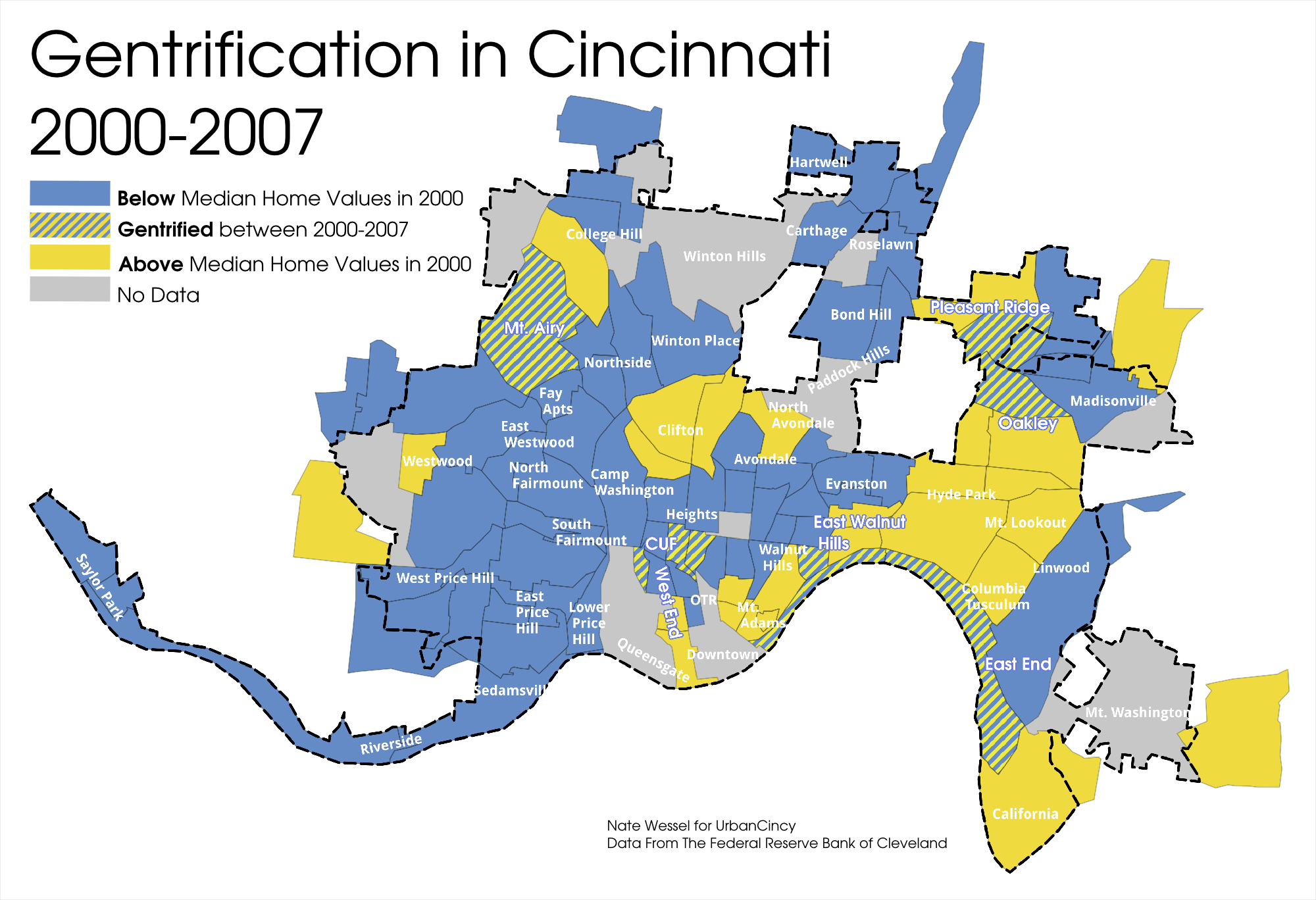

The Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland noted gentrification in a wide variety of Cincinnati neighborhoods between 2000 and 2007. Map produced by Nate Wessel for UrbanCincy.

What is even more intriguing about the report’s findings is that original residents who moved from the gentrifying neighborhood, who many would consider displaced residents, experienced a 1.5 point higher credit score improvement than those who did not move.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland provided UrbanCincy with the data broken out by Census tract for Cincinnati. Approximately 72% of the city’s 104 Census tracts are defined as low-price, and of those 75 Census tracts with home valuation data, nine were found to have gentrified between 2000 and 2007.

When examined more closely it becomes clear that the neighborhoods experiencing the biggest gains in home value and income in Cincinnati are those that are in the center city. Specifically, and perhaps not surprisingly, five of the nine are located in the neighborhoods of Clifton Heights, East Walnut Hills, Fairview, University Heights and the East End. Outside of the center city, Pleasant Ridge, Oakley, Columbia Tusculum and Mt. Airy also experienced gentrification over the past decade.

Community council leaders for these neighborhoods did not respond to multiple requests for comments from UrbanCincy.

Unfortunately, the two neighborhoods where many expect gentrification has occurred most – Downtown and Over-the-Rhine – did not have median home value data available for the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland to study.

While the report has generally positive findings about the impacts of gentrification, Cincinnati is at a disadvantage when it comes to improving the financial health of its neighborhoods.

According to the report, the percentage of low-price Census tracts in Cincinnati beneath the median home value of the metropolitan area is 14 percentage points higher than the national average, and the rate at which Census tracts are gentrifying in the Great Lakes region is approximately 4.5 points lower than the national average.

“I don’t have a clue what Hartley meant by the phrase ‘neighborhoods with a potential for gentrification’ but the assertion that 95% do in Baltimore is rather ludicrous given the high rate of abandonment,” Dr. Varady scoffed. “Baltimore certainly can use more gentrification but how the city can promote this is an open question.”

With the nine identified neighborhoods in Cincinnati spread throughout a mix of expected and unexpected locations, it is probably safe to say that the Census tracts in Downtown and Over-the-Rhine also gentrified during this period, or have since 2007.

Change in cities is inevitable, but whether these changes sweeping Cincinnati are good, bad or indifferent is probably still open for spirited discussion among those most interested.

“In general I think that gentrification presents benefits and costs,” Dr. Varady concluded. “Anyone who says it is all bad or all good is not contributing to the debate.”