In the mid-2000s, ODOT designed a $1 billion reconstruction of I-75 between the Ohio River and I-275 that attracted little attention from the Cincinnati media. Who would win and who would lose as access points were shifted, added, or permanently closed?

Aside from a successful effort in 2006 by OKI to retain access at Galbraith Road over ODOT’s objections, virtually no public objections were made as multi-million dollar contracts were let; and work commenced in 2011 on a mega-project that will shape Cincinnati’s traffic patterns and property values for the next fifty years.

ODOT’s design strategy for the Mill Creek Expressway (Western Hills viaduct to Paddock Rd.) and Thru the Valley (Paddock Rd. to I-275) projects aimed to improve capacity and safety by reducing points of access and mitigating complex merging movements. This means most of I-75’s left-side ramps will be rebuilt as right-side ramps, and odd partial interchanges, such as the Towne Street ramps in Elmwood Place and the famous southbound “canyon” ramps in Lockland, will be permanently removed.

ODOT has already closed a lightly-used ramp providing access to I-75 southbound from Spring Grove Avenue, and another exiting I-74 westbound at Powers Street in Northside.

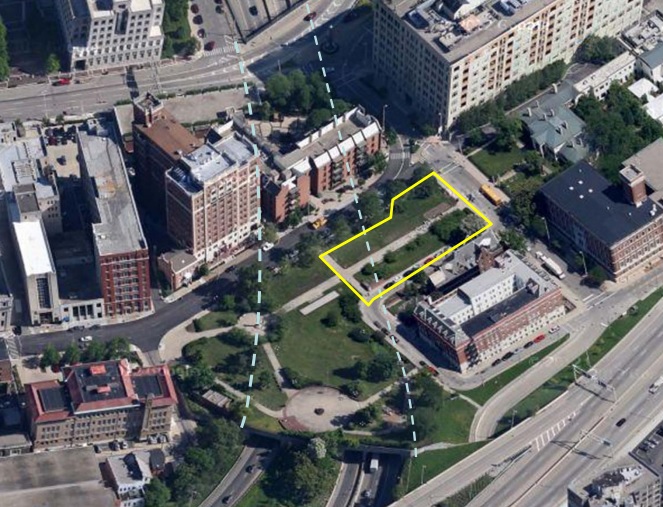

In 2016, ODOT plans to permanently close two ramps near Cincinnati State Technical and Community College. One provides access to I-75 northbound from Central Parkway, while the other provides access to Central Parkway from I-74. The planned closure of this final ramp – an unremarkable 250-foot deck girder overpass spanning I-75 near the Ludlow Viaduct – has been public knowledge for nearly a decade, but only recently has its closure generated opposition.

Evidence suggests that replacement of Central Parkway access from I-74 was discussed in the mid-2000s via an aerial structure approximately 10 times longer than the current 250-foot overpass. A drawing from February 2007 illustrates that the flyover ramp would have diverged from I-74 near the Colerain and Beekman Street interchange, bridged Elmore Street, then deposited traffic onto Central Parkway very close to the location of the current ramp.

Despite an effort led by Cincinnati State and then Vice Mayor Roxanne Qualls (D) several years ago, ODOT has not capitulated to recent pleas by Cincinnati State and the City of Cincinnati to reestablish the access provided by the existing 250-foot exit ramp with a similar ramp forking from the planned I-74 east to I-75 north ramp.

Such a ramp would not comply with current Federal Highway Administration guidelines, which discourage local access ramps built in close proximity to “system” interchanges, and local access ramps that diverge or join system interchange ramps. In fact, construction of a new ramp similar to what currently exists would violate Section 6.2.11 and Section 6.2 of FHWA code.

ODOT’s refusal to permit reconstruction of the I-74 ramp to Central Parkway, however, is inconsistent with its recent activities elsewhere in the state.

As part of the $200+ million reconstruction of the I-71/I-670 interchange in Columbus, an exit ramp to Leonard Avenue, a local residential street, was built in the middle of a “system” interchange. No reciprocal access to I-71 south was built, meaning this new ramp violates two sections of the FHWA’s guidelines and created a new situation identical on paper to the one ODOT seeks to eliminate in Cincinnati.

Access to Cincinnati State Community College from I-74 after 2017

In 2015, the City of Cincinnati, with the endorsement of Mayor John Cranley (D), outlined plans for an entirely new 2,500-foot viaduct connecting Elmore Street in South Cumminsville with Central Parkway at Cincinnati State. Ostensibly the proposed viaduct will restore the easy access from I-74 that Cincinnati State will lose in 2017; and, according to Cincinnati State President O’Dell Owens, help attract and retain students who commute from the city’s western suburbs.

To be sure, the proposed viaduct will improve access to I-74 westbound, as no direct access currently exists. But inbound travel will be significantly slower than what presently exists, and not much faster than what would exist if it weren’t built at all.

Perhaps the Elmore Street Viaduct, or something similar to it, could have been better integrated with the I-74 Beekman Street ramps if access to Central Parkway had been deemed a priority 10 years ago – instead ODOT completed a significant rebuilt of the interchange in 2014 with no provision for a new viaduct to Central Parkway.

Access to Cincinnati State Community College from I-75 after 2017

Missing from the Elmore Street Viaduct conversation, however, is the character of Cincinnati’s access from I-75. Currently, commuters from city’s northern neighborhoods must pass Cincinnati State on southbound I-75, exit at Hopple Street, then backtrack one mile north along Central Parkway. Commuters using I-75 north must exit a mile south of the college, traverse the new jug handle connection between Martin Lurther King Drive and Central Parkway, then drive one mile north.

If the current circuitous path I-75 commuters use to reach Cincinnati State isn’t discouraging attendance by prospective students from those neighborhoods, why does President Owens contend that use of the very same Hopple Street exit ramp will discourage I-74 commuters?

Why No Ludlow Avenue Interchange?

Missing from I-75’s initial 1950s construction, and its current reconstruction, is a full interchange at Ludlow Avenue. A new diamond interchange on the Ludlow Viaduct would have created ideal access to Cincinnati State, a new alternative route to the University of Cincinnati and the hospitals, and significantly increased property values in Northside.

Construction of a new interchange at Ludlow Avenue does not appear to have entered into ODOT’s conversations a decade ago, nor did construction of an interchange at Vine Street in St. Bernard.

MetroMoves and the Future of the Rapid Transit Right-of-Way

In 2002, Hamilton County voters defeated MetroMoves, a half-cent sales tax that would have funded improved countywide bus service and construction of various modern streetcar and light rail lines. The initiative planned for the convergence of two light rail lines above the I-75/I-74 interchange that would have provided direct access to Cincinnati State via a station located on the west face of its hill above Central Parkway.

The convergence of two lines just north of the property promised frequent train service for the community college, even during off-peak hours; however, no call for improved public transportation has been heard from those currently pushing for the Elmore Street Viaduct.

What’s more, there has been no call to incorporate a provision for rail transit on the proposed Elmore Street Viaduct. When looking at ODOT’s 2007 drawing, it is plain to see how the proposed structure could be integrated into the light rail network, thus eliminating the high expense of a dedicated light rail viaduct over the I-75/74 interchange in the future.

Meanwhile, ODOT’s reconstruction of I-75 will leave the old Rapid Transit Loop right-of-way mostly intact between the subway portals and Cincinnati State – meaning only a 100-foot bridge over Marshall Avenue will be necessary to construct a fully grade-separated surface line between the subway portals and Cincinnati State.

EDITORIAL NOTE: After this article was published, Mayor John Cranley’s office, through spokesperson Kevin Osborne, contacted UrbanCincy and provided additional information regarding the efforts of then Vice Mayor Roxanne Qualls to piece together funding for a smaller, yet similar project years ago. This article has been updated to reflect that reality.