In 1997 officials from the City of Cincinnati and Hamilton County set out on a path to transform the city’s central riverfront. What became known as the Cincinnati Central Riverfront Plan laid out a bold vision to accomplish just that, and has now been recognized by the American Planning Association (APA) for the implementation of the plan first laid out nearly two decades ago.

The APA will present local leaders with the National Planning Excellence Award for Implementation at its annual conference to be held in Chicago on April 16.

“The Cincinnati Central Riverfront redevelopment is an excellent example of plan brought to reality,” Ann C. Bagley, 2013 APA Awards Jury chair, stated in a prepared release. “The fact that this development happened during an economic downturn demonstrates the strength of the plan and the importance of the public commitment that brought it into being.”

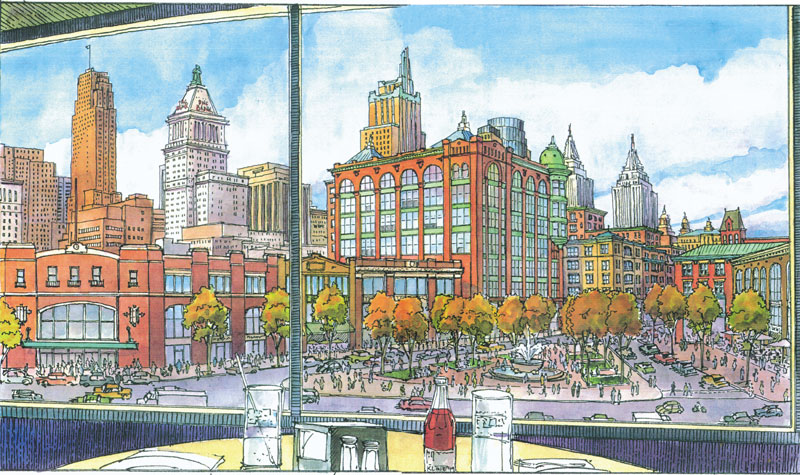

Cincinnati’s central riverfront has shifted dramatically from its form in the 1980s [LEFT], to that of the 2010s [RIGHT].

Local leaders have taken an incremental approach towards implementing the vision laid out in the Cincinnati Central Riverfront Plan. Between 1998 and 2002, the first major investments included the reconstruction Fort Washington Way (FWW), and the development of Paul Brown Stadium, Great American Ball Park, and the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center.

The consolidated FWW opened up dozens of acres of waterfront property, and the development of two stadiums and a major museum were intended to serve as cultural and entertainment anchors that would draw Cincinnatians back to the riverfront.

These significant public investments laid a critical foundation that would enable the next phase of work, historically located in one of the most flood-prone areas of the city, out of the 500-year floodplain.

Once a private development team had been selected, the City of Cincinnati and Hamilton County began to work with Carter-Dawson on the construction of the plan’s most ambitious element known as The Banks.

Phase two of The Banks will deliver another 300 residential units along with more than 60,000 square feet of commercial space, and a future office tower.

The $91 million first phase of the mixed-use development began in 2007 and resulted in 300 apartments, 76,000 square feet of commercial space, and 6,000 structured parking spaces. Emboldened by the success of phase one, developers are set to break ground on phase two in the coming months which will include another 300 residential units and more than 60,000 square feet of commercial space.

Two office towers, a hotel and townhomes are still to come within the first two phases of The Banks. At ultimate build out, officials envision The Banks to result in $600 million worth of private investment and become the home for more than 3,000 residents.

Meanwhile, construction of the $120 million, 45-acre Smale Riverfront Park is progressing concurrently with the development of The Banks. To date, the first phase of the new central riverfront park has been completed and work is beginning on phase two. Future phases will be timed with future construction of The Banks, and as funding is allocated.

“In planning terms, a project that goes from a concept to implementation in less than 20 years is impressive to say the least,” stated Todd Kinskey, Executive Director of the Hamilton County Regional Planning Commission. “It is that much more impressive because, in this case, the implementation involved seemingly insurmountable physical, economic, and political barriers.”

The early discussions surrounding The Banks, however, were tumultuous at best as local leaders grappled with complaints about too much office space being introduced into an already competitive marketplace.

The original vision of the Cincinnati Central Riverfront Plan [LEFT] included more traditional types of architecture with greater use of natural building materials [RIGHT].

“The current plan to include 30-story buildings along the riverfront would harm downtown and violate the riverfront plans adopted by the community many years ago,” then Councilman Jeff Berding (D) told the Business Courier in 2007. “We need to remember that the plan adopted several years ago was not simply pulled out of the air, but was the result of intense public input and driven by professional urban planners.”

While design elements may not be of the same caliber as those originally envisioned, the urban form of the private investment appears to be as desired. But even more gratifying than that, for many of the early people involved in the planning, it is that the project has happened against all odds and skeptics.

“The successful implementation of the plan is the result of unprecedented cooperation between the city, the county and their partners,” exclaimed Vice Mayor Qualls (C), who was one of the original driving forces behind the development of the Cincinnati Central Riverfront Plan.

Her thoughts were further validated when Bagley concluded, “The fact that this development happened during an economic downturn demonstrates the strength of the plan and the importance of the public commitment that brought it into being.”

In addition to the future phases of the Smale Riverfront Park and The Banks, city leaders are now soliciting ideas for how to cap a 300-foot span of FWW. City and county officials say that the work to cap the short stretch of interstate will commence once a design is in place, and funding has been secured.