After a three-year planning process, Cincinnati’s first comprehensive plan in 32 years will be shared with the city’s Planning Commission. The hearing marks a ceremonious occasion for city employees that have worked tirelessly on the plan since Mayor Mark Mallory (D) tasked them to work with the community on putting together an updated plan for the Queen City.

The City of Cincinnati Planning Department will share the 228-page document with the Planning Commission at 6pm today at City Hall (map). From there the document will move on to City Council’s Livable Communities Committee, and then the full City Council for approval where officials do not expect much, if any, pushback from the nine-member elected body. After formal approval from City Council, the document will become Cincinnati’s policy guide for everything from financial to environmental decisions, and beyond.

The city’s new comprehensive plan, Plan Cincinnati, places a strong focus on creating and building upon walkable neighborhood centers. Photograph by Randy A. Simes for UrbanCincy.

The tone for the city’s new vision is set early and often throughout the document stating, “The vision for the future of Cincinnati is focused on an unapologetic drive to create and sustain a thriving inclusive urban community, where engaged people and memorable places are paramount, where creativity and innovation thrive, and where local pride and confidence are contagious.”

The focus on a comprehensive urban approach is a bold diversion from Mayor Charlie Luken’s (D) administration which ultimately left the city without a Planning Department after a heated debate over whether to allow Vandercar Holdings to build a suburban-style development at what is now the Center of Cincinnati big-box development.

In the early 2000s, Vandercar had agreed to go along with Cincinnati’s Planning Department and build a mixed-use development on the site. Disagreements over the project led to a change of heart by the development team, and a strong reaction by both Mayor Luken and then City Manager Valerie Lemmie to dismantle the city’s planning department.

The renewed focus on urbanism in the Plan Cincinnati document establishes 11 goals that range from growing the city’s population, to becoming more aggressive with economic development, to developing a culture of health. One of the key goals set out by Plan Cincinnati calls on leadership to build on the city’s existing assets. To that end, the plan identified 40 Neighborhood Centers that should serve as the diverse, walkable centers of activity throughout the city.

Of those 40 nodes, approximately 28 percent are recognized as “urban” neighborhood centers while the remainder are identified as “traditional” neighborhood centers.

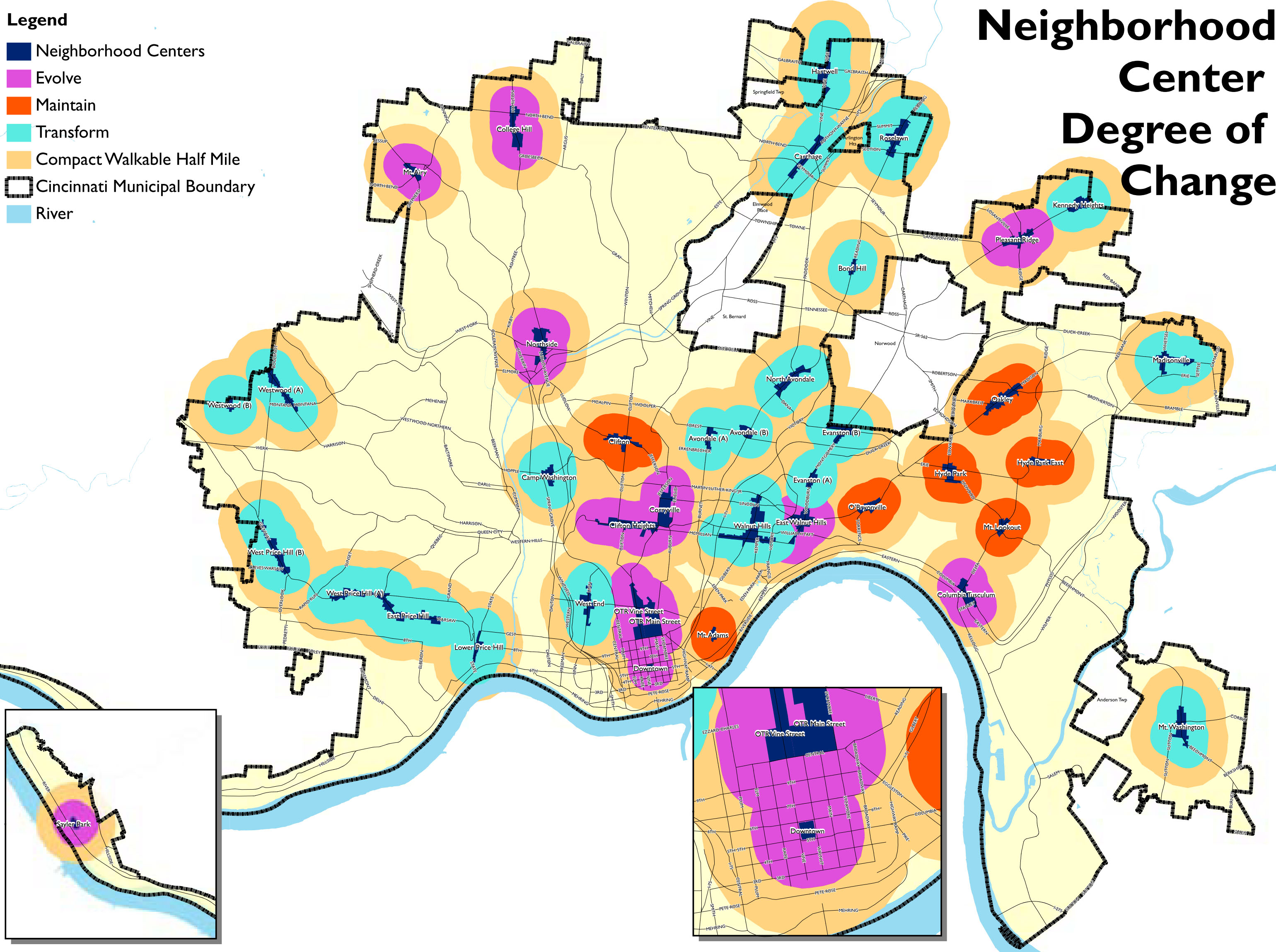

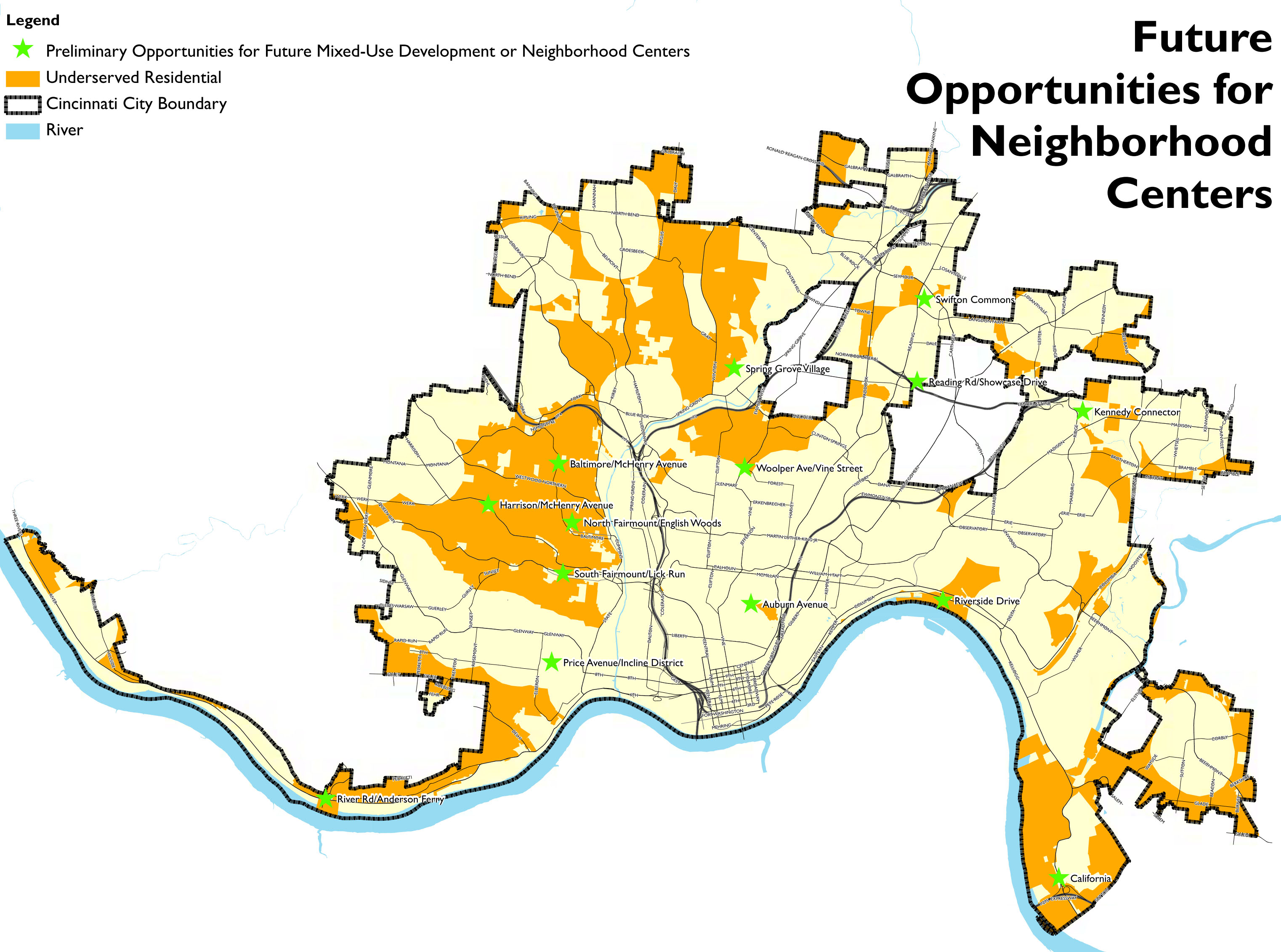

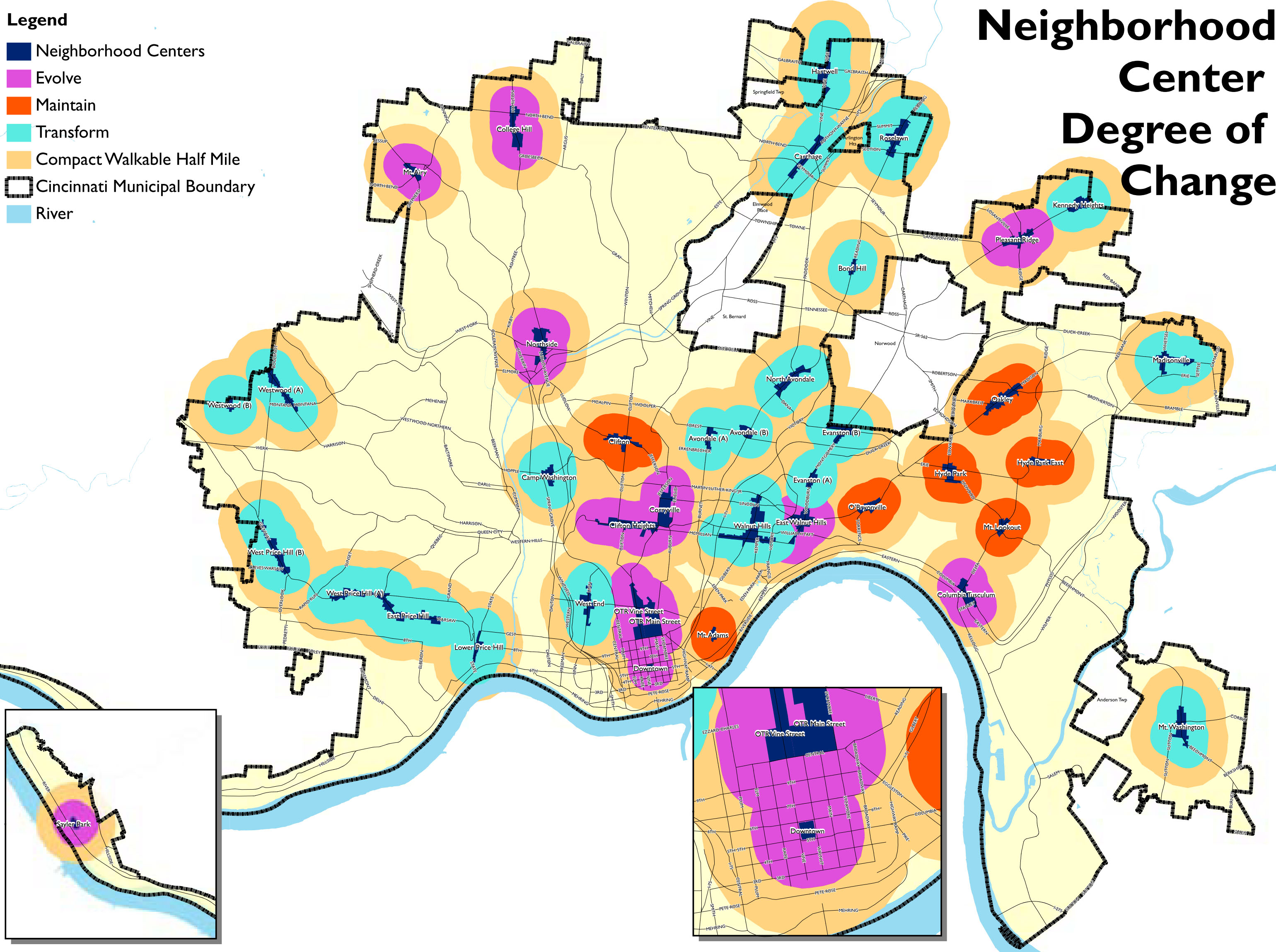

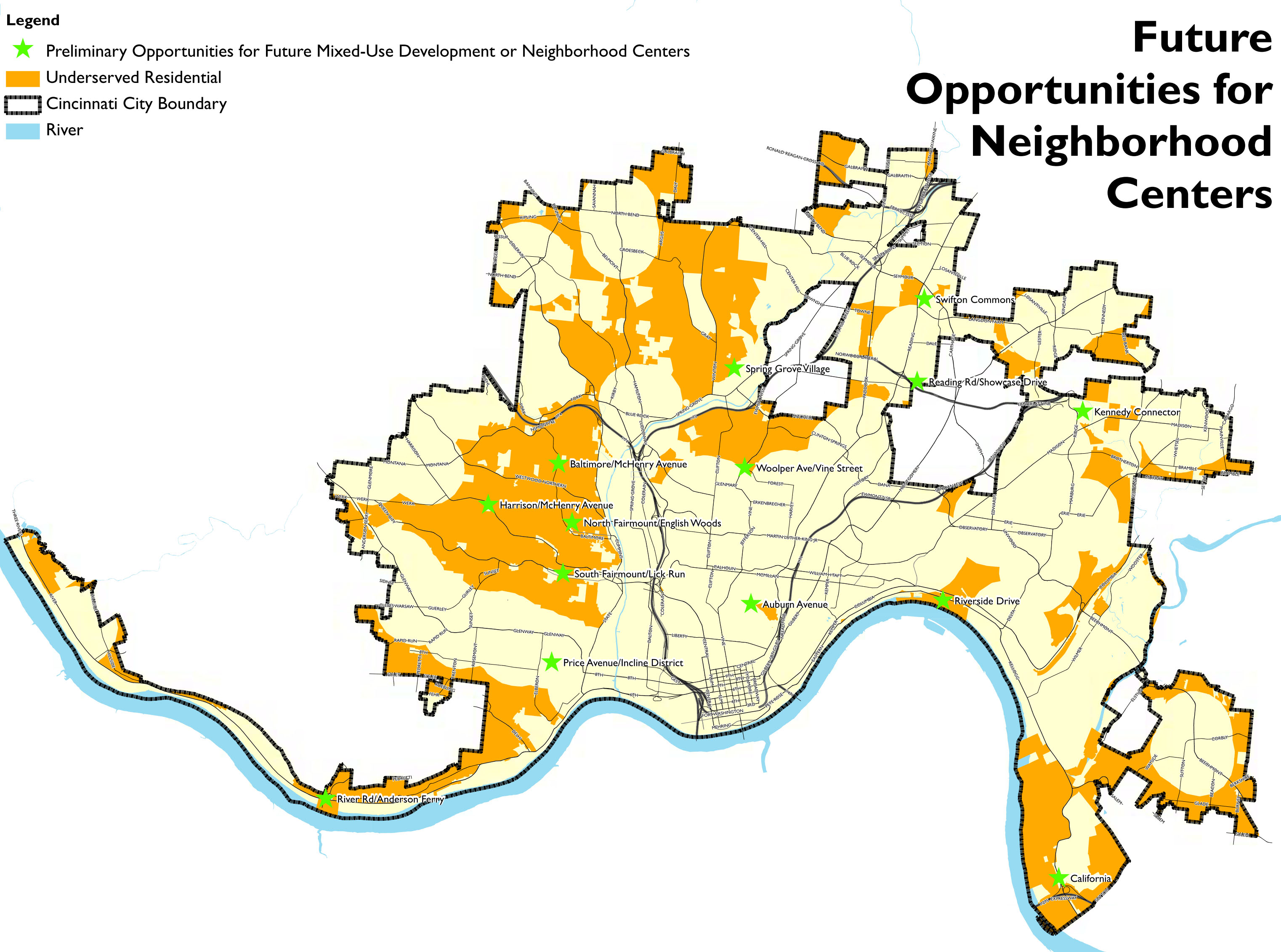

Plan Cincinnati recognized 40 Neighborhood Centers throughout the city [LEFT], and identified 14 preliminary areas to examine for future investments that could lead to new Neighborhood Centers [RIGHT]. Maps provided.

“Our neighborhoods are structured around centers of activity that contain all of the amenities that we need to go about our daily life,” the Plan Cincinnati document states. “We will focus our development on these centers of activity, and strategically select areas for new growth.”

From there the plan recognizes which of those neighborhood centers are doing a good job at serving as diverse, walkable centers. Seven are seen as well off and simply needing maintenance; 12 are identified as areas that need to evolve and become more walkable, and the remaining 21 are called on to be transformed with large-scale changes such as infill, redevelopment, and public improvements.

“We will permeate our neighborhoods with compact, walkable mixed-use development, bikable streets and trails, and transit of all types (such as bus, light rail, bus rapid transit, light rail transit, streetcar/circulator vehicles, and passenger rail),” declares the Plan Cincinnati document. “The development of a Complete Streets policy and adoption of a form-based code are tools that will help reach this goal.”

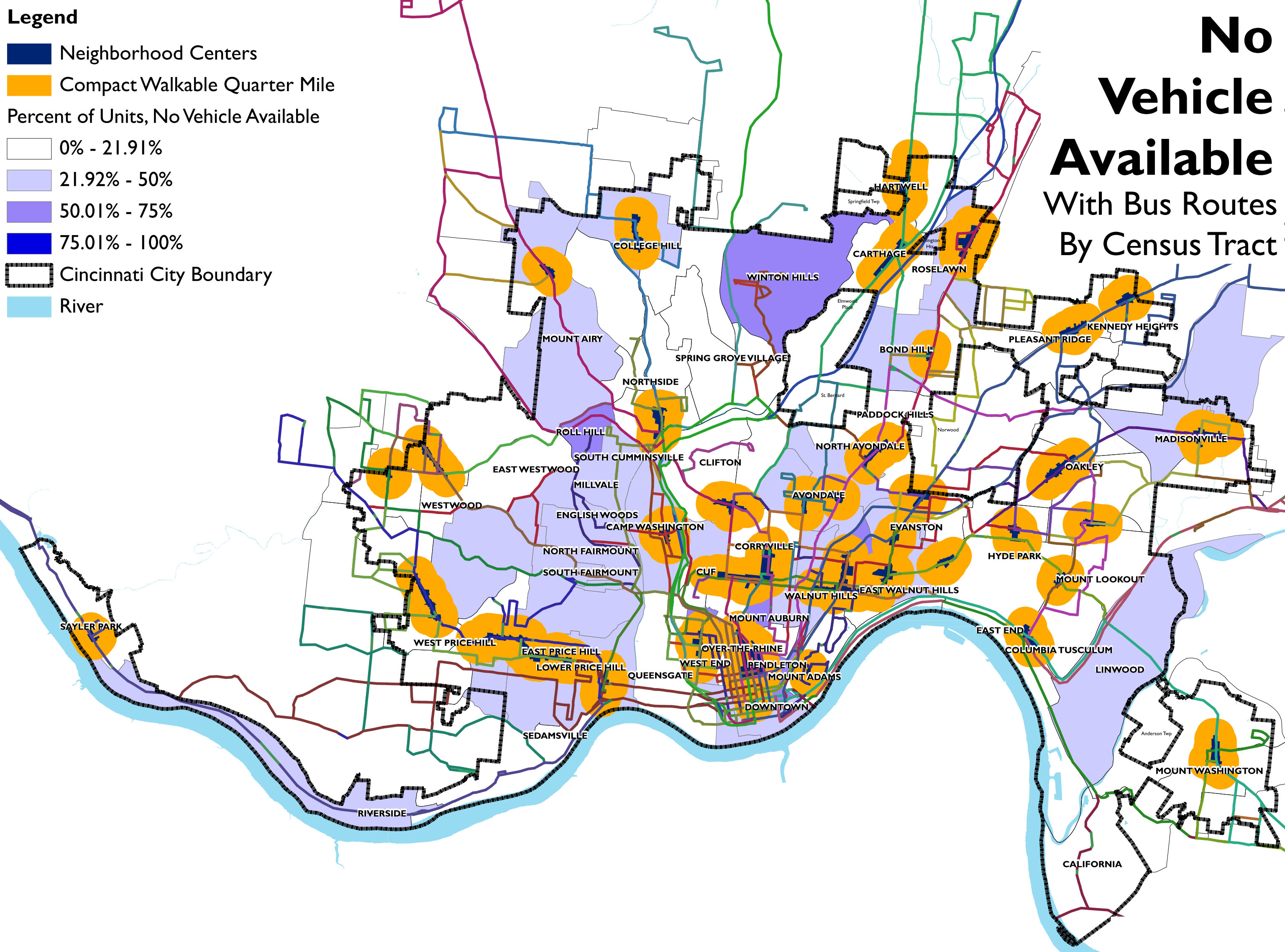

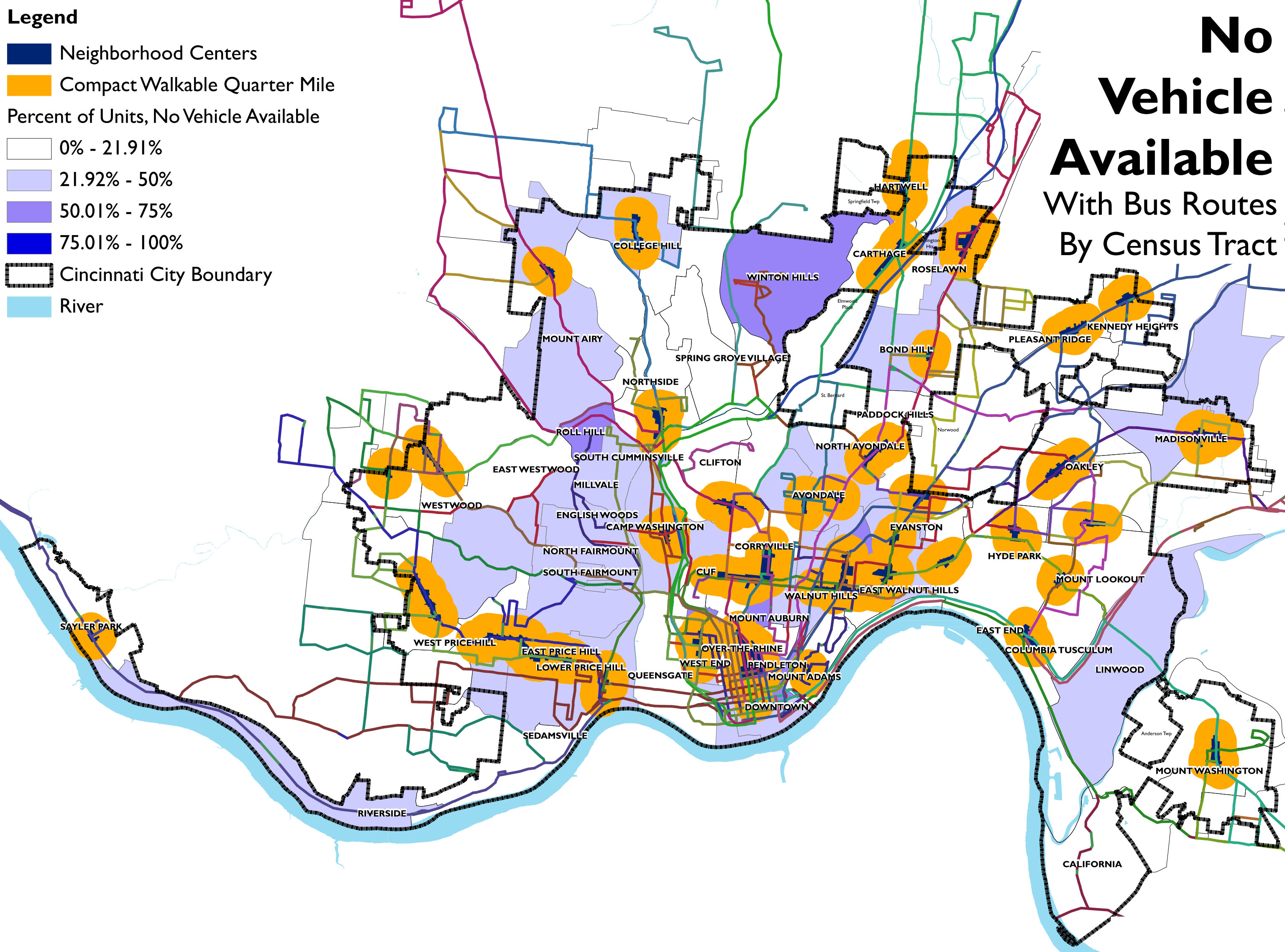

A sobering fact, presented within the plan, is that roughly 22 percent of all Cincinnati households have no automobile, while only a percentage of those households have safe and easy access to the jobs, goods and services they need.

Approximately 22% of Cincinnati households do not own a car, and are not within easy access to the goods and services they need. Map provided.

To help solve that issue, city planners hope to build upon the goal of creating a healthy, sustainable community by eliminating food deserts and providing fresh produce within a half-mile, or 15-minute walk or transit ride, from all residential areas.

City planners acknowledge, however, that building upon existing assets will not be enough in order to create the envisioned outcomes identified within PLAN Cincinnati. As a result, the document identifies 14 preliminary opportunities (see second map) for future mixed-use development that can eventually serve as new neighborhood centers where they are currently lacking.

While the visioning document looks to be unapologetic about its urbanist movement, it also looks to firmly establish Cincinnati as the unapologetic leader within the larger region, stating that consolidation of government services and municipal boundaries will be efforts led by the City of Cincinnati.

PLAN Cincinnati goes into much greater depth on many more topics. Those interested in learning more can download the entire document online, or attend tonight’s Planning Commission meeting where staff will be on hand to answer questions afterwards.