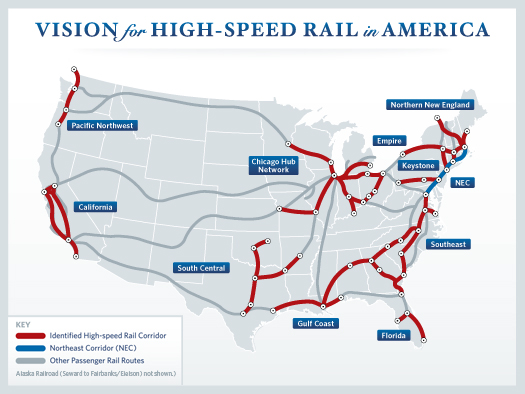

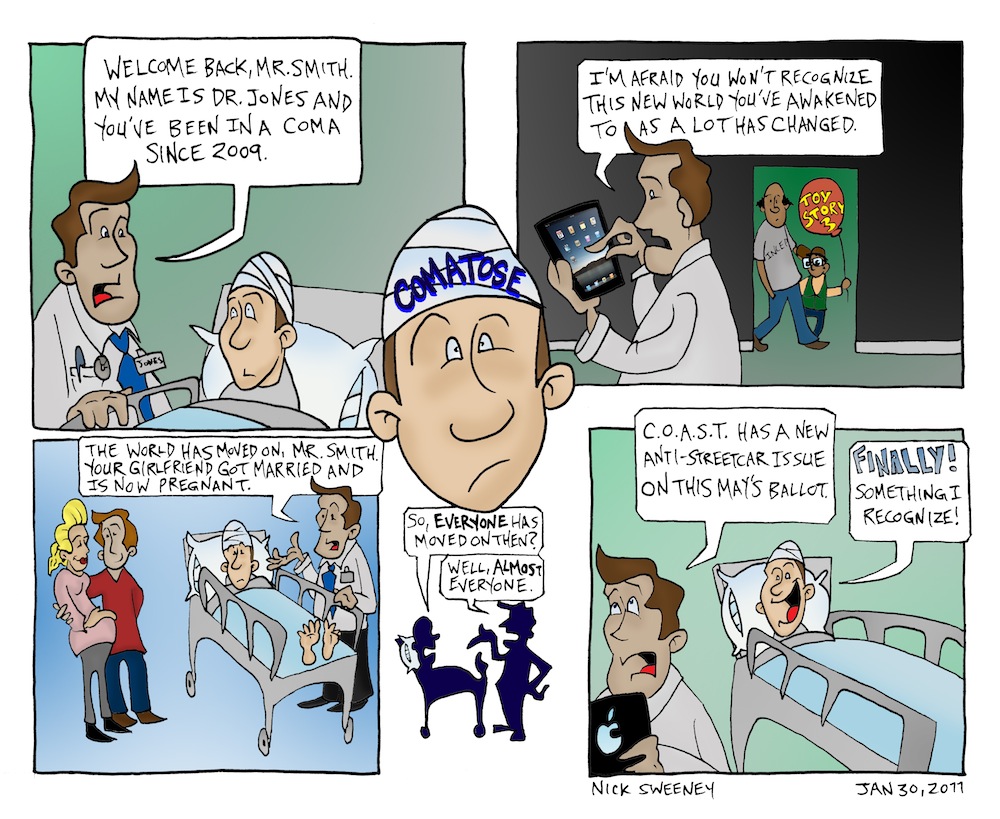

As Cincinnati’s transport officials prep for the introduction of a modern streetcar line in 2012, and potential bus rapid transit in the coming years, further improvements need to be made to the network. One of the most striking improvements needed is a new payment system for those using Cincinnati’s various bus systems, the streetcar, taxis and bike and car share programs if they ever materialize.

In Korea the T-Money Card rules. Based off of a simple yet wildly successful tap-and-go pay system, the card can be used all over the place. In Seoul, one can use the T-Money Card to pay for taxis, trains, buses, museums, vending machines, stores, fines, taxes and more. And in addition to the transit stations, the card can be purchased at convenience stores all over the metropolis.

The functionality is brilliant, and policy makers there have decided to use the data collected, from the system, to determine funding allocation for transit routes. This means that the most heavily used routes and stations get the most investment. Furthermore, the efficient tap-and-go system allows for quick payments and faster boarding on crowded buses and trains.

London has recently decided to go a step further. Their new Oyster Card not only offer the same benefits of the T-Money Card (minus taxi use), but the system also allows for people with contactless bank cards to use those as their tap-and-go payment. Both the T-Money and Oyster cards offer customization as well. The Oyster Card has custom holders and card designs, while the T-Money Card has custom card designs and sizings.

There are flaws with both systems from which Cincinnati can learn as it upgrades its payment system over the coming years. The first lesson is to have broad appeal. Cincinnati should engage various stakeholders to help develop a system pay card that can be used on all of the regional bus systems, streetcars, pedicabs and water taxis. While doing this the city should keep in mind future integration with any bike or car sharing programs.

Flexibility should also be a part of the new payment system being discussed in Cincinnati. The beauty of electronic pay is that the payment plans are limitless. A rider should be able to choose from buying a certain number of trips, specified time frame (i.e. 30 days) or even just a certain dollar amount. Offering riders choices will help fuel ridership and attract riders of choice.

While Cincinnati has been late to the game when it comes to upgrade its decades-old payment system, it allows transport officials to learn from others around the country and world. Innovative technologies and approaches should be used to make sure Cincinnati is on the cutting edge. London and Seoul have great payment system solutions, and Cincinnati should combine them for an even better one.