In 2011 Nate Wessel sought out to change the way Cincinnati mapped its transit. In a region with multiple transit operators that all use traditional bus mapping visuals, it was quite the daunting task. But after successfully raising more than $2,000 on Kickstarter, Wessel was able to fund his effort to print tens of thousands of his newly designed maps that ultimately received national praise.

Since that time he has continued his quest to improve the visual nature of map-making in Cincinnati, including serving as UrbanCincy’s official contributing cartographer, but he also embarked on another major endeavor. Instead of a transit map with bus frequencies, Wessel this time focused his energies on creating a new regional bike network map.

“Imagine someone kept taking, and reproducing and sharing, very unflattering photos of you or someone you loved. If you’re like me, you’d probably let the first one slide,” Wessel stated. “Maybe it was an accident, but by the fifth or sixth one, you’d start noticing a pattern and you’d start getting kind of miffed about it.”

This is the feeling the twenty-something urban planner, cartographer and fashion designer felt about the region’s existing bike maps, and he wanted to take control of the situation and improve it.

“This is a subtle visual game and words won’t do,” Wessel explained. “You need to make your own photo that shows the beauty you see in what you love; and then get other people to see what you see.”

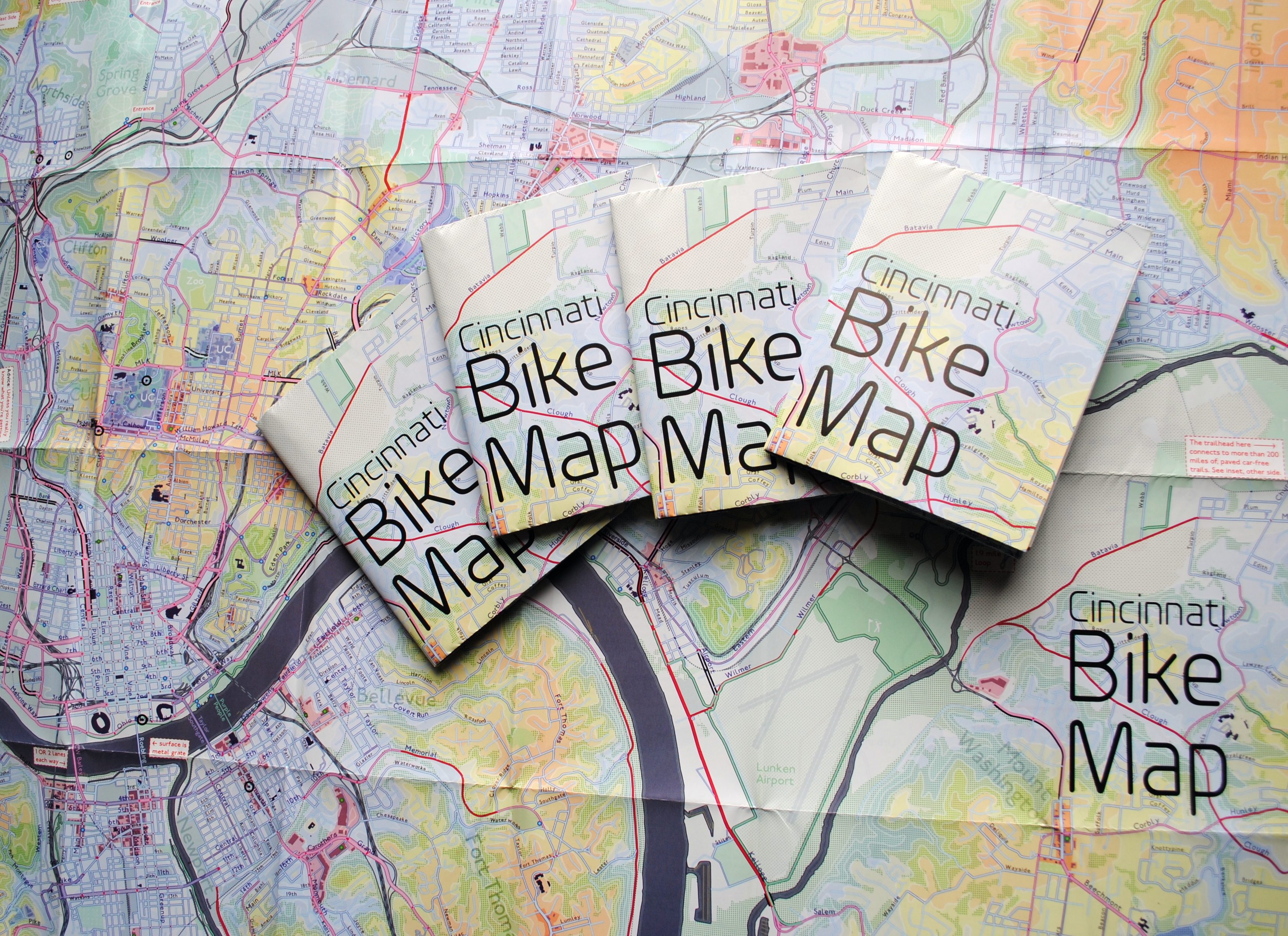

One of the ways to accomplish that, he says, is to get the maps into people’s hands – digital maps are not enough. While the physical presence of a printed map gives it a sense of permanency and seriousness, producing a hard copy map also comes with its challenges.

After finishing the design for the Cincinnati Bike Map, Wessel said that he received feedback from the binder recommending a redesign to better accommodate the way the paper would fold, but that it was too late in the process. As a result, he wishes the maps folded a bit better, but that he is otherwise quite pleased with the final product. Perhaps leading to that feeling of satisfaction, however, is the fact that no compromise was needed since the project was entirely self-funded.

“Both times I’ve raised money for these projects it was in advance of having a real demonstrable product,” said Wessel. “In neither project have I ever had to check anything with a sponsor, supervisor or co-designer. The maps were totally my own in both cases, held to my own standards alone and uncompromised. That is very unusual for print maps.”

While quite unusual, it was a situation he preferred. In fact, Wessel says that a local organization very generously offered to fully fund the printing of Cincinnati Bike Map should he work with their graphic designer. A generous offer indeed, but one that came with risks that the final product not turn out as originally envisioned.

The release of the new regional bike map last month comes at a time when Cincinnati is in the national spotlight for its dramatic gains in bike ridership and development of new bike infrastructure.

Now that the project is complete, the goal now shifts to distributing the stack of Cincinnati Bike Maps that now exist. In addition to distributing the maps to local bike shops and organizations, Wessel is also mailing out copies of the map. His hope is that new or unfamiliar riders feel empowered by the maps, and that experienced riders use them to explore new routes throughout the region.

“Regular cyclists have found their favorite routes and will probably stick with what they know,” said Wessel. “Though, I totally discovered Fort Thomas through this map. Every map I’d seen made it look like a pretty crappy, suburban place to ride and I always avoided it; but the streets are beautifully wooded and very slow with 25mph speed limits.

Of course, all of this would not have been possible without access to the treasure trove of data on-hand at Cincinnati City Hall, and with the OKI Regional Council of Governments.

Those who would like to get a free copy of the Cincinnati Bike Map can do so by emailing Nate Wessel at bike756@gmail.com and informing him of your name, how many copies you want, and the address to which he can ship them.