Research continues to show that Americans are driving less, but are biking, walking and using transit more. This is true in Cincinnati to the extent that transit ridership has increased in recent years.

While originally attributed to the economic downturn at the beginning of the century, these trends have continued while the economy has rebounded – leading many to believe it is an indication of new market forces being driven by aging Baby Boomers and emerging Millennials. Perhaps predictably so, governments have been slow to change with the changing economic forces.

Despite a growing number of trips for biking, walking and transit, funding has not increased correspondingly. In fact, many communities have seen funding for these non-automotive forms of transportation decrease as governments have worked to cut spending at all levels. This, new research finds, is only exacerbating the problem of having underfunded these modes of transportation for many years.

“Conventional statistics tend to under report active travel because most travel surveys under-count shorter trips (those within a traffic analysis zone), off-peak trips, non-work trips, travel by children, and recreational travel,” stated Todd Litman, Executive Director of the Victoria Transport Policy Institute, in a summary of his report entitled Whose Roads? Evaluating Bicyclists’ and Pedestrians’ Right to Use of Public Roadways.

“More comprehensive surveys indicate that active travel is two to four times more common than conventional surveys indicate, so if statistics indicate that only 5% of trips are by active modes, the actual amount is probably 10-20%.”

Litman indicates that funding levels tend to be much lower than even the low 5% trip share estimates, and recommends changing those levels to reflect not only the current trip share levels, but those that could be achieved should investments be made.

Unequal Funding Allocations at Regional Level

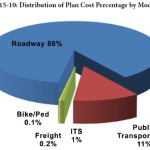

At the local level, the same situation of unequal funding allocation exists. In the 2040 Regional Transportation Plan, developed by the OKI Regional Council of Governments, approximately 88% of the nearly $21.5 billion in funding is recommended to go toward roadway projects, just 11% to transit and a mere 0.1% to bicycle and pedestrian improvements.

While the level of investment in transit appears closely aligned with current ridership levels for commute-related trips, it is far below ideal levels for bicycle and pedestrian investments.

“Relatively aggressive pedestrian and cycling improvement programs only cost about 1-4% of the total per capita roadway expenditures, or just 4-10% of general taxes spent on local roadways,” Litman contests. “Since walking and cycling represent about 12% of total trips, and a much larger share of short urban trips, and since most North American communities have under-invested in walking and cycling facilities for the last half-century, much larger investments in walking and cycling facilities can be justified to meet user demands and for fairness sake.”

OKI leadership contends that the organization’s regional planning document does not accurately reflect the level of investment being made in bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure, noting that many of the “roadway projects” in their plan actually include bike and pedestrian elements.

To that end, some recent improvements have been made with regard to bicycle infrastructure. The City of Cincinnati has installed around 40 miles of new on-street bike lanes or paths over the past several years, and has plans to install a total of 290 miles by 2025. The City’s Bicycle Transportation Plan, however, has been plagued by a lack of funding and has been relegated to only moving forward when roadway resurfacing projects emerge.

Not everyone is convinced, however, that enough is being done in terms of the overall investment needed for bike and pedestrian improvements.

Implications for Regional Transit

Of the money being recommended for transit investments, not including operations, approximately 96% is targeted for the contentious Oasis Line – a commuter rail line connecting Cincinnati’s far eastern suburbs with downtown.

Furthermore, the vast majority of OKI’s recommended transit funding is aimed to pay for ongoing operations – not pay for system expansions or improvements.

This grim financial picture for transit gets even worse when considering contributions from state and local governments.

In Ohio, the City of Cincinnati is the only local jurisdiction that provides a dedicated stream of funding for the Southwest Ohio Regional Transit Authority (SORTA), which was also recently found to perform better than average given its low levels of investment from local, regional and state partners.

In Kentucky, meanwhile, communities struggle with state law that prohibits any dedicated source of transit funding – thus forcing the Transit Authority of Northern Kentucky (TANK) to go before the state legislature every year seeking money, similar to how Amtrak must annually go before Congress.

Impact on Environmental Justice Populations

These dire funding and political situations have led to Greater Cincinnati taking the title of being the most populated region in North America without any rail transit; while even far less populated regions advance their own regional transit plans.

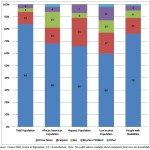

What makes the figures more troubling is that those most affected by the imbalanced funding appropriations are minority, low-income and disabled populations. While only 6% of the region takes transit, bikes or walks to work each day, that number escalates to 17% for African Americans, 11% for Hispanics and 10% for people with disabilities; while low-income commuters see that number spike to 21%. Quite simply, the lack of funding for non-automotive forms of transportation is most damaging to those who can least afford it.

The results of this inequality sparked a recent lawsuit by the ACLU of Wisconsin Foundation and Midwest Environmental Advocates filed a complaint against the Wisconsin Department of Transportation over a $2 billion highway interchange project. In MICAH & Black Health Coalition of Wisconsin v. Gottleib, the ACLU states:

“WisDOT explicitly refused to consider transit expansion (or transit in any way) as part of this proposal. This will further widen the already large gap between transit-dependent communities of color and disproportionately white suburban commuters. The ACLU of Wisconsin Foundation was one of the organizations that have complained about the government’s decision-making and reporting process, as well as how the project would exacerbate segregation and disparities in transportation access for low-income people to jobs.”

And while some of these mode shares may seem low, it has been noted by the U.S. National Household Travel Survey that commute trips are the lowest for walking and biking, while personal trips and trips less than one mile are significantly higher for both modes.

“In much of the region where we have large concentrations of EJ populations the sidewalk network is already quite developed, the roadway network is quite developed and available to bicyclists and the transit service is good,” countered Bob Koehler, Deputy Executive Director at OKI. “We do, as a community, need to do a better job at sharing the road and being aware of pedestrians to make these facilities better for all modes.”

Highway Building Frenzy

Even though young people are increasingly either delaying or choosing not to get a driver’s license at all, user fees collected from the gas tax continue to decline, total vehicle miles traveled (VMT) has been decreasing since 2007 and annualized VMT has been decreasing for nearly a decade, the nation and Cincinnati region continue to build new capacity.

Of the roughly $8.3 billion being recommended for roadway projects in OKI’s planning documents, approximately 73% of that is targeted for additional lanes, new facilities or new interchanges, while reconstruction and improvements to existing roadways account for the rest.

“Although VMT may be slightly declining in recent years in some parts of the country this may not be a long-term trend. Clearly the region has many needs,” explained Brian Cunningham, Director of Communications at OKI. “This plan addresses the significant existing safety and congestion needs. The plan is updated every four years and will provide an opportunity to revisit the assumptions.”

Litman argues that shifting some of the investment from roadways to bicycle and pedestrian projects due to their proven ability to reduce congestion and improve safety not only for bicyclists and pedestrians, but motorists as well. He also believes that such policy directives empower people by giving them the ability to choose between multiple transportation options for each of their trips.

“It is important to recognize the unique and important roles that active modes [biking and walking] play in an efficient and equitable transportation system, and the various benefits that can result when walking and cycling are improved, including indirect benefits to people who do not currently use those modes,” Litman concluded.

“Just as it would be inefficient to force travelers to walk or bike for trips most efficiently made by motorized modes, it is inefficient and unfair to force travelers to drive for trips most efficiently made by active modes, for example, if children must be chauffeured to local destinations because their communities lack sidewalks, or if people must drive to recreational trails due to inadequate sidewalks and paths near their homes.”

This information comes at a time when the region has been identified as failing to develop walkable urban places, and thus putting itself behind its national competitors.