Between two of Over-the-Rhine’s most treasured attractions is a Cincinnati Center City Development Corporation (3CDC) proposal currently on hold. As a result, the non-profit development corporation will either need to obtain a new funding source or the project will need to be “a little more within the scale of the existing market.”

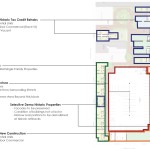

The current proposal for the mixed-use project at Fifteenth and Race includes over 300 parking spaces, 57 residential units, and almost 22,000 square feet of commercial space. With the project now on hold, now is the time to step back and critically evaluate a major development in the heart of Over-the-Rhine.

The unnamed development sits primarily along Fifteenth Street, between Pleasant and Race Streets, and would occupy almost an entire city block with a massive parking garage and what can otherwise be described as a lackluster design. Think Mercer Commons 2.0.

Stand at the northern edge of Washington Park and look down Pleasant Street. If your eyes are better than mine, you’ll see Findlay Market. If you’d like to walk there, it is only a leisurely five to ten minute stroll. This proposed development’s car-centric design places a parking garage exit on Fifteenth Street, and would force vehicular traffic onto one of Over-the-Rhine’s most important pedestrian axes.

Additionally, the garage packs in 200 more vehicles than is mandated by law, forces the partial demolition of two historic structures, and limits the available commercial and residential space sandwiched between the phase one Cincinnati Streetcar route. If the streetcar should increase property value as predicted, a parking garage may not be the best use of land for such a prominent location along the line.

As is currently designed, the buildings that would wrap the garage present themselves as a homogeneous wall. This character contrasts heavily with the existing fabric that presents gaps between buildings, portals to interior courtyards, and strong visual relief. While the roof line makes an attempt at creating rhythm in concert with windows, its variation is not enough to mask that it is one big building.

These characteristics detract from the pedestrian scale, though the new construction hints at these qualities with balconies, recessed entries, and slightly offset building faces. These expressions are more akin to developments at The Banks and U Square at The Loop, and are a cheap imitation of Over-the-Rhine’s authenticity.

Along Pleasant Street, the Fifteenth and Race townhomes are compressed by the large, central parking garage. The private walk at the townhomes’ rear is noted as a ‘garden space’ but these spaces are approximately 10 feet wide and will be shadowed by a three-and-a-half-story parking garage. Along the street, the crosses and boxes highlighting the townhomes’ windows are wholly contemporary, which are expressions out of place on a building that is neither modern nor traditional; it is non-committal.

It should be noted that an entire block design is a difficult task in Over-the-Rhine because its designation as a historic district stems from the collection of smaller individual buildings built over time. Furthermore, the neighborhood’s historic character, established before the invention of the automobile, does not easily accommodate cars.

However, there will be a need for more parking, and the Over-the-Rhine Comprehensive Plan recognizes this, but states that new parking should be done “without impacting the urban fabric or historic character of the neighborhood.”

Individually rehabbed buildings do not typically have the potential to alter a neighborhood’s character, but when large-scale development is proposed, community members should have a place at the table.

When asked about developers engaging community stakeholders, Steve Hampton, Executive Director of the Brewery District Community Urban Redevelopment Corporation, says, “If there’s one place for community outreach it is in large-scale development because of the unique architecture, historic neighborhood, and diversity of people in Over-the-Rhine.”

In the case of this Fifteenth and Race development, the first stages of community engagement were initiated by Over-the-Rhine Community Housing (OTRCH) and Schickel Design, who completed the Pleasant Street Vision Study (PSVS) in 2013.

While the proposed development incorporates all of the individual elements from the PSVS, it is not in the spirit of the pedestrian-focused Pleasant Street Vision Study and on a very different scale. The size and location of the parking garage is a major difference between the 3CDC proposal and the PSVS, and Mary Rivers, of OTRCH, noted that this is a big issue for many people.

Of course there is a gap between a vision study that outlines a community’s desires or needs, and the market forces that drive a real development, but there are various ways a community should be engaged in a project of this scale.

While OTRCH held focus groups prior to beginning the award-winning City Home project one block south along Pleasant Street, Rivers said that 3CDC did not engage OTRCH until after the current plans had been unveiled.

Rivers said, “We asked a diversity of people, ‘What do you like in Over-the-Rhine? What are you looking for in a home?’ Their answers ultimately influenced the design.” This type of engagement is not easy; and Rivers acknowledged that the best way to engage a community is on big issues not the details.

3CDC needs to step up, engage community stakeholders, and propose a design that is more respectful to Over-the-Rhine’s residents, and its unique architectural and urban form.