Three percent of the Earth’s surface is developed land, not including farmland. While this may seem like a small percentage, it is the type of development that has created major problems for sustainable living conditions.

With an emphasis on single-family residential developments, auto-oriented planning, and an enormous supply of open land, it has become common knowledge that American cities are more sprawling than their global counterparts. These development patterns, although not entirely confined to the United States, are unique to American planning and have resulted in more sprawl and less sustainable development over the years.

This can plainly be seen by comparing dense European suburbs to American post-WWII sprawling suburbs. Further emphasizing this point today is that while the European Union has identified the percentage of developed land as one of 155 sustainable development indicators in terms of humanity’s ecological footprint, the United States has only noted its land use patterns but not used them as a factor in planning.

A new study, released in March by environmental engineering professors Dr. Giorgos Mountrakis and Dr. George Grekousis at the SUNY College of Environmental Science & Forestry, confirms the premise that America’s population growth does in fact consistently result in increasing land consumption, with the results varying between different states and counties where land management policies differ.

Their study used satellite imagery of the contiguous United States to measure the exact amount of developed land (DL) in 2,909 counties, excluding the outliers in the 100 least populated and 100 most populated counties. They then compared imagery from 2001 to the 2000 Census count in order to rank each county on what they call its DL efficiency. To make for more accurate comparisons, they then compared the results of each given county to the 100 counties closest to it in size (50 smaller and 50 larger).

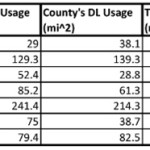

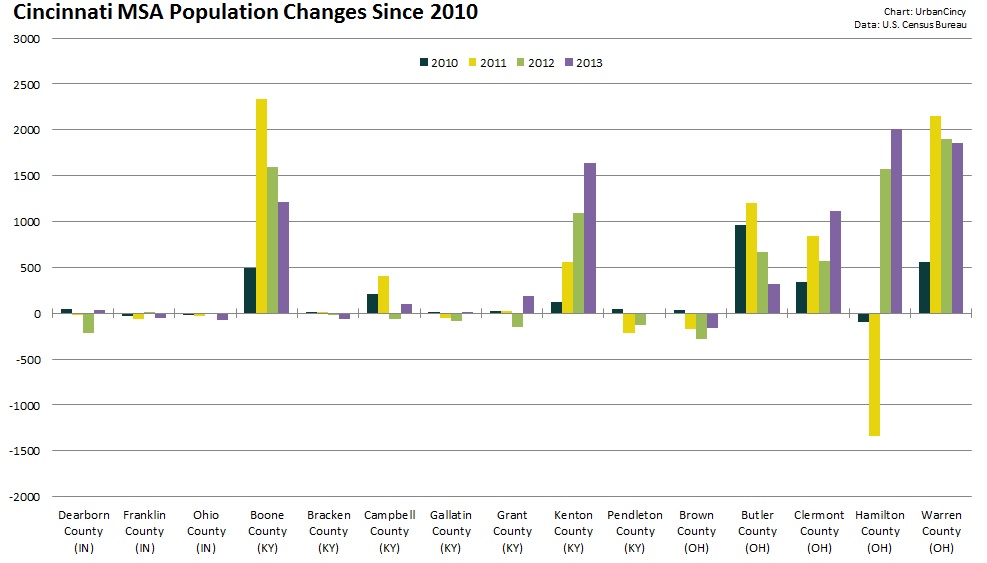

Using this standard measurement, when Hamilton County was measured it came in at 43rd in its peer group. In this study, those counties with higher scores are considered to be more inefficiently developed. This means that Hamilton County came in slightly ahead of the curve when compared to its peers, which had an average rank of 51.

While the study shines a light on population growth and development patterns, it also reveals several socio-economic differences between similarly sized counties. Perhaps the most significant finding was that there seems to be a linear correlation between DL usages and population growth. For example, the researchers found that population growth of a county can be estimated by comparing its current DL usage to its past usage to then produce an estimate within a 95% confidence level. The larger the city gets, the more sprawling it will become at a consistent rate.

The study also confirmed that, compared to other developed countries, the United States is more inefficiently developed and that American cities tend to grow horizontally as population rises instead of vertically.

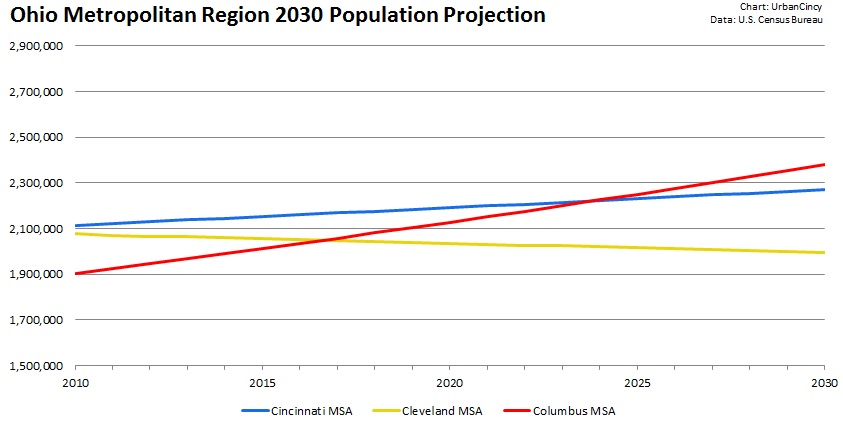

With this in mind, the report projects that the anticipated 30% population growth, between 2003 and 2030, will result in a 51% increase in land consumption. This equates to 44.5 million acres of land converted to residential and commercial development, and follows a trend of Rural Non-Metropolitan Statistical Areas developing land at nearly twice the rate of urban and suburban Metropolitan Statistical Areas.

One of the commonalities amongst low land consumption MSA counties, the SUNY researchers found, was that they were mostly located in states and cities with stronger planning agencies and urban growth boundaries. Furthermore, nearly all of the cities in these counties also had experienced rapid growth pre-automobile.

With a ranking of 43, Hamilton County comes in slightly better than the national average in its peer group. Elsewhere in Ohio, Clermont County ranked at 20 in its peer group, perhaps due to its makeup of 19th century towns and propensity of farms. And reflecting the dominance of post-war suburban housing, Butler and Warren Counties bring up the back of the pack at 62 and 55, respectively.

The three urban counties in Northern Kentucky, meanwhile, followed the larger trend for Kentucky overall and were found to be very efficient in their land use when compared to their peer groups.

For comparison, the Cincinnati metropolitan region as a whole scored better than those in Seattle, St. Louis, Kansas City, Orlando, Oklahoma City and Charlotte.

When Cincinnati’s population peaked in the mid-1950’s, it had over 500,000 residents within the city limits, while that number stood at just under 300,000 in the 2010 Census. This means that as the urban core continues to revitalize and add population, land that has become underutilized or abandoned will have the potential to be redeveloped, adding to the city and county’s density, and thus further improving its ranking.